Why Hypoglycemia Is More Dangerous for Older Adults

Low blood sugar isn’t just uncomfortable for older adults with diabetes-it can be life-threatening. When blood glucose drops below 70 mg/dL, it’s called hypoglycemia. For someone in their 70s or 80s, even a mild drop can lead to confusion, falls, or a heart attack. Unlike younger people who feel shaky or sweaty before their blood sugar crashes, many older adults don’t notice anything until it’s too late. By the time they feel dizzy or confused, their glucose might already be below 50 mg/dL. That’s why hypoglycemia in seniors is often called a "silent killer."

Studies show older adults have 2.3 times more low blood sugar episodes than younger people with diabetes. And it’s not just because they take more insulin. Their bodies don’t respond the same way. The hormones that normally kick in to raise blood sugar-like epinephrine and glucagon-work 30% to 50% slower in older adults. Add to that kidney or liver problems, which are common with age, and the body loses even more ability to recover from a low.

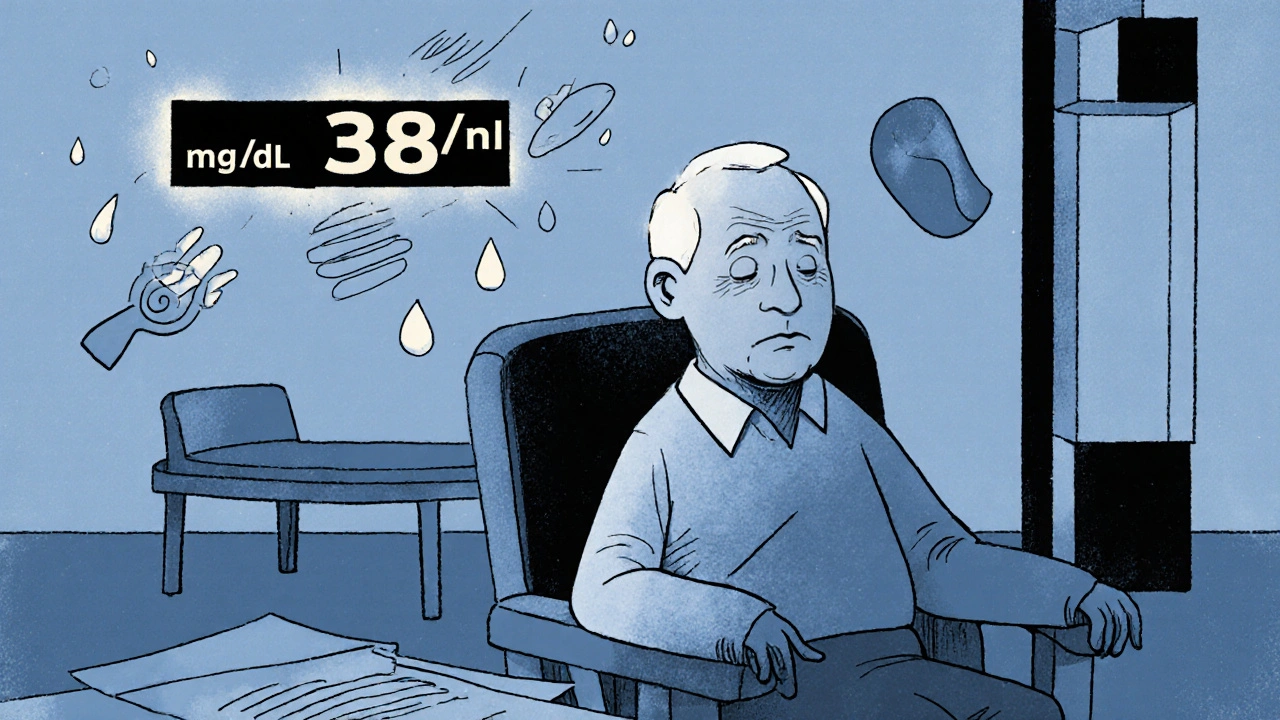

The Hidden Symptoms No One Talks About

Most people think low blood sugar means sweating, trembling, or a racing heart. But in older adults, those classic signs often disappear. Instead, they might seem "off"-forgetful, irritable, or unusually quiet. One caregiver described her 84-year-old father: "He just sat in his chair, staring at the wall. I thought he was zoning out. His glucose was 38 mg/dL."

Up to 60% of hypoglycemic episodes in seniors go unnoticed or unreported. Why? Because they don’t feel the warning signs. This is called hypoglycemia unawareness. About 1 in 5 older adults with type 2 diabetes and 1 in 4 with type 1 diabetes lose their ability to sense low blood sugar. For those with dementia or depression, it’s even worse. They can’t tell you they feel weak. They might not even remember eating lunch.

Medications That Put Seniors at Risk

Not all diabetes drugs are created equal when it comes to safety in older adults. Sulfonylureas-like glyburide, glipizide, and gliclazide-are common, cheap, and effective. But glyburide, in particular, is dangerous. It stays in the body too long, especially if kidneys aren’t working well. Studies show it increases the risk of severe hypoglycemia by 50% compared to glipizide in seniors.

The American Geriatrics Society’s Beers Criteria lists glyburide as a medication to avoid in older adults. Yet, many are still prescribed it because doctors don’t realize the risk. Insulin is another big culprit. A 2023 study found that reducing insulin doses from 40 units to 20 units per day cut weekly lows by 80%-without making A1c worse. The goal isn’t perfection. It’s safety.

Other high-risk drugs include meglitinides (like repaglinide) and certain combination pills. Metformin, GLP-1 agonists, and SGLT2 inhibitors are much safer because they rarely cause low blood sugar on their own. If you’re over 70 and on a sulfonylurea or long-acting insulin, ask your doctor: "Is this the safest option for me?"

What Happens When Blood Sugar Drops Too Low

A single episode of severe hypoglycemia doesn’t just scare you-it changes your body. Each low increases your risk of:

- 40% higher chance of falling

- 25% higher chance of breaking a hip

- 30% higher chance of a heart attack or stroke

- 1.8 times higher risk of developing new memory problems in just two years

One man in his late 70s broke his hip walking to the kitchen for juice after a low. He didn’t realize he was hypoglycemic until he hit the floor. Hospital stays after these events often lead to a downward spiral: loss of mobility, infection, depression, and even earlier death. A five-year study found seniors who had severe lows were 2.5 times more likely to die than those who didn’t-even after adjusting for other illnesses.

The scary part? Most of these events happen at home, not in the hospital. Emergency rooms only see the worst cases. The real problem-the hundreds of unnoticed lows each year-is invisible to the healthcare system.

How to Build a Personalized Prevention Plan

Preventing hypoglycemia isn’t about cutting sugar or eating more snacks. It’s about smart, individualized planning. The American Diabetes Association recommends a four-step approach:

- Know your risk. Have you had a low in the past year? Do you live alone? Do you have kidney disease, dementia, or take five or more medications? If yes, you’re at high risk.

- Check your meds. Ask your doctor to review every diabetes drug. Can any be stopped? Can glyburide be switched to glipizide? Can insulin doses be lowered?

- Set realistic goals. For healthy seniors, an A1c under 7% is fine. For those with heart disease, dementia, or frailty, aim for 7.5% to 8.5%. Tight control is dangerous. Comfort and safety matter more.

- Use monitoring tools. Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) like the Dexcom G7 or FreeStyle Libre 3 can alert you before a low hits. But Medicare only covers them for people on insulin. Many seniors on sulfonylureas are left out-even though they’re just as likely to crash.

A real-world study in Pennsylvania showed that after three doctor visits focused on medication review and goal-setting, 46% fewer seniors were at risk for hypoglycemia in just six months. And their A1c barely changed-down 0.3%. That’s the win: fewer lows, no trade-off in control.

What Families and Caregivers Need to Know

If you care for an older adult with diabetes, you’re their first line of defense. Learn the signs: confusion, slurred speech, odd behavior, or not answering when called. Don’t wait for trembling. That’s a late sign.

Keep fast-acting sugar on hand: juice boxes, glucose tablets, or honey packets. But here’s the key: if they’re confused or can’t swallow, don’t give them anything by mouth. Use a glucagon kit. The new nasal glucagon (Baqsimi) is easy-just spray one dose into the nose. No needles. No prep. It works in under five minutes.

One caregiver said: "My mother couldn’t swallow juice after a low. The nasal glucagon saved her. We keep it next to her coffee maker now."

Also, talk to your doctor about the TRIM-HYPO survey. It’s a simple questionnaire that measures how much hypoglycemia affects daily life. Using it helps doctors see the real impact-and makes it easier to justify changing medications.

What’s Changing in 2025

Doctors are finally catching up. The ADA now recommends that older adults aim for 50% of their day (12 hours) in the target range of 70-180 mg/dL. That’s not perfection-it’s protection. They also want less than 1% of the day spent below 54 mg/dL.

New tools are coming. A dual-hormone artificial pancreas (insulin + glucagon) is in clinical trials for seniors. It could automatically stop insulin and release glucagon before a low hits. But it won’t be widely available until 2026.

The biggest shift? Moving away from A1c as the main goal. Time-in-range is becoming the new standard. It tells you how often glucose stays safe-not just the average.

Final Advice: Safety Over Perfection

If you’re managing diabetes in an older adult, remember: a slightly higher A1c is better than a trip to the ER. A1c 8% with no lows is far safer than A1c 6.5% with three severe episodes a year.

Don’t be afraid to ask: "Can we lower this dose?" "Is this medicine still necessary?" "What’s the safest goal for someone my age?"

Most seniors don’t want to be perfect. They want to stay independent. To walk to the kitchen. To remember their grandchild’s name. To sleep through the night without fear. That’s the real goal of diabetes care in older adults-not numbers on a screen. It’s life.

Jennifer Griffith

November 25, 2025 AT 16:50Timothy Sadleir

November 26, 2025 AT 19:58Roscoe Howard

November 27, 2025 AT 18:54Patricia McElhinney

November 28, 2025 AT 11:08Agastya Shukla

November 28, 2025 AT 11:55Pallab Dasgupta

November 28, 2025 AT 19:19Ellen Sales

November 30, 2025 AT 06:18Emily Craig

December 1, 2025 AT 04:17Karen Willie

December 2, 2025 AT 03:40Shivam Goel

December 3, 2025 AT 23:09Amy Hutchinson

December 4, 2025 AT 14:28Archana Jha

December 5, 2025 AT 10:35