CDI Risk Calculator for Antibiotic Prescriptions

Based on published data from studies of antibiotic-associated CDI risk

Clinical context and patient-specific factors should always be considered

When prescribing clarithromycin is a macrolide antibiotic used for respiratory infections, skin infections, and Helicobacter pylori eradication, doctors often think about efficacy and common side effects like nausea or taste changes. What many patients and clinicians overlook is the drug’s link to a serious gut problem called Clostridioides difficile infection (C. diff) - an antibiotic‑associated diarrhea that can lead to colitis, sepsis, or even death. This article walks through the science, the numbers, and practical steps you can take to keep the risk low.

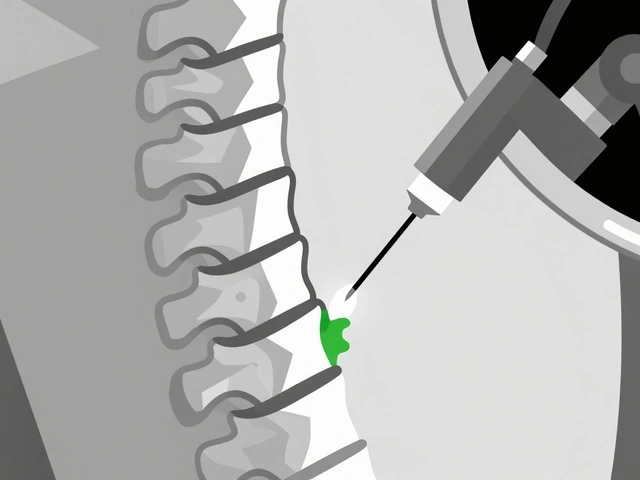

Why antibiotics can trigger C. diff

Antibiotics wipe out bacteria that help protect the gut. When the balance is disturbed, C. diff finds a niche, multiplies, and releases toxins that irritate the colon. Not every antibiotic carries the same danger; the risk depends on how broadly the drug kills gut microbes and how long it stays in the system.

Clarithromycin’s place among gut‑disrupting drugs

Clarithromycin is considered a moderate‑risk macrolide. It targets a wide range of gram‑positive and some gram‑negative bacteria, but its effect on anaerobes (the group that includes C. diff) is less severe than clindamycin or fluoroquinolones. Still, clinical data show a measurable uptick in CDI cases after clarithromycin courses, especially in hospitals where patients are already vulnerable.

Evidence from studies

Several retrospective cohort studies from the last decade give us a clear picture:

- A 2021 analysis of 45,000 hospital stays found a 1.2% CDI incidence within 30 days of clarithromycin use, compared with 0.5% for patients on penicillins.

- A 2023 meta‑analysis of 12 randomized trials reported an odds ratio of 1.8 (95% CI 1.3‑2.5) for CDI when clarithromycin was part of the regimen versus no macrolide.

- In outpatient settings, the risk drops to roughly 0.3% but remains higher than for narrow‑spectrum agents like amoxicillin.

These numbers sound small, but when you multiply them by the millions of prescriptions written each year, the public‑health impact becomes significant.

How clarithromycin compares with other high‑risk antibiotics

| Antibiotic | Approx. CDI incidence (%) | Typical clinical use |

|---|---|---|

| Clindamycin | 2.5 | Skin, bone, anaerobic infections |

| Fluoroquinolones | 2.0 | UTI, respiratory, prostatitis |

| Clarithromycin | 1.2 | Respiratory, H. pylori, atypical pneumonia |

| Cephalosporins (3rd‑gen) | 1.0 | Severe infections, meningitis |

| Penicillins (broad‑spectrum) | 0.5 | Strep throat, otitis media |

The table makes it clear: clarithromycin sits in the middle of the risk spectrum. It’s safer than clindamycin and fluoroquinolones but riskier than many penicillins and newer cephalosporins.

Who is most vulnerable?

Not everyone who takes clarithromycin will get C. diff. Certain groups face higher odds:

- Older adults (especially >65 years)

- Patients with recent hospitalization or surgery

- Those on proton‑pump inhibitors, which raise stomach pH

- Individuals with a history of CDI

- People with weakened immune systems (e.g., chemotherapy, steroids)

If any of these factors apply, clinicians should weigh the benefits of clarithromycin against the added CDI risk.

Practical steps to lower the risk

Here’s a checklist you can use at the bedside or in outpatient clinics:

- Antibiotic stewardship: Reserve clarithromycin for cases where it’s truly needed-e.g., macrolide‑resistant atypical pneumonia.

- Shortest effective duration: Aim for 5‑7 days unless guidelines dictate longer therapy.

- Assess probiotic use: Evidence from a 2022 trial shows that Saccharomyces boulardii taken alongside antibiotics cuts CDI rates by about 40% in high‑risk patients.

- Monitor for early signs: Diarrhea that persists beyond 48 hours warrants stool testing for C. diff toxins.

- Infection control: Hand‑washing with soap, contact precautions, and thorough terminal cleaning in hospitals reduce transmission.

When CDI is confirmed, the first‑line treatments are oral vancomycin or fidaxomicin, followed by metronidazole for mild cases. Early therapy shortens hospital stay and lowers mortality.

Guideline snapshot (2024‑2025)

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) both recommend:

- Avoiding high‑risk antibiotics like clindamycin and fluoroquinolones when a safer alternative exists.

- Using clarithromycin only when the infection is proven or strongly suspected to be caused by susceptible organisms.

- Implementing rapid PCR testing for C. diff toxins to guide early discontinuation of the offending antibiotic.

Following these guidelines can shave weeks off a patient’s recovery and curb the spread of CDI in healthcare facilities.

Bottom line for clinicians and patients

Clarithromycin is a useful drug, but it carries a measurable CDI risk that climbs in older or hospitalized patients. By practicing judicious prescribing, limiting treatment length, and staying alert to early diarrhea, you can keep that risk low while still treating the infection effectively.

How common is C. difficile infection after a short course of clarithromycin?

In community settings, the incidence is about 0.3% after a 5‑day course. In hospitals, it rises to roughly 1.2% within 30 days.

Can probiotics prevent CDI when taking clarithromycin?

Studies suggest that Saccharomyces boulardii or a high‑dose Lactobacillus preparation can lower the odds by up to 40% in high‑risk patients, but they are not a substitute for careful antibiotic use.

What are the first‑line treatments for a clarithromycin‑associated CDI?

Oral vancomycin (125 mg four times daily) is preferred. Fidaxomicin is an alternative, especially for recurrent cases. Metronidazole is reserved for mild disease.

Should I stop clarithromycin if I develop mild diarrhea?

If diarrhea persists beyond 48 hours, get a stool test for C. diff toxins. If the test is negative, you can usually finish the course, but discuss alternatives with your doctor.

Are there cheaper alternatives with lower CDI risk?

For many respiratory infections, amoxicillin‑clavulanate or a narrow‑spectrum penicillin offers similar coverage with a CDI incidence around 0.5%. Always let a clinician decide based on culture results.

Marrisa Moccasin

October 22, 2025 AT 12:15Did you ever notice how the pharma giants hide the real C. diff numbers behind layers of jargon!!!??

Caleb Clark

November 4, 2025 AT 10:53Alright team, let’s get real about clarithromycin – it’s a solid choice when you’ve got atypical pneumonia, but you gotta watch those gut microbes. The data shows a 1.2% CDI rate in hospitals, which isn’t negligible. I always tell my patients to stick to the shortest effective course, usually five to seven days, no more. If you’re on a proton‑pump inhibitor, consider stepping down if possible – that’s a big risk factor. Probiotics like Saccharomyces boulardii can cut the odds, so I recommend them for high‑risk folks. Remember, early detection is key – if diarrhea lasts more than 48 hours, test for C. diff toxins pronto. Hand‑washing and contact precautions in the clinic are non‑negotiable, especially after antibiotic courses. Stay motivated, keep prescribing wisely, and you’ll save lives while still killing those bugs!

Eileen Peck

November 17, 2025 AT 10:30I totally get where you’re coming from – clarithromycin is useful, but the CDI risk is real, especially for the elderly. In my experience, adding a probiotic can be a game‑changer for patients with multiple risk factors. It’s also worth checking if the patient is on a PPI – sometimes you can deprescribe that safely. The guideline snapshot you quoted aligns with what most infectious disease societies recommend. Keeping the treatment duration short, as you mentioned, really does the trick. If you see persistent diarrhea, don’t wait – order a stool toxin assay right away. Also, educate patients about the signs of C. diff early on; they’ll be more likely to report it. Overall, a balanced approach saves both the gut flora and the patient’s health.

Oliver Johnson

November 30, 2025 AT 10:08Sure, clarithromycin works, but why keep using a drug that sits in the middle of the risk table? Simpler drugs can do the job without the gut drama. If you’re scared of C. diff, just pick a penicillin when it covers the bug. Less hype, less risk. The numbers don’t lie – clindamycin and fluoroquinolones are worse, but why settle for “moderate” when you can go low?

Taylor Haven

December 13, 2025 AT 09:45Let me lay it out plain and simple, because the truth about antibiotics is being hidden behind a veil of corporate silence. Clarithromycin, hailed as a miracle drug, is in fact a ticking time bomb for the gut, especially in the hands of a healthcare system that profits from prolonged treatments. Think about it: every prescription adds to a cumulative burden that pushes vulnerable patients over the edge into a full‑blown C. diff infection. The data isn’t a fluke – a 2021 study of 45,000 hospital stays found a 1.2% incidence, more than double the risk with a simple penicillin. That’s not a coincidence; it’s a systemic failure to prioritize patient safety over pharmaceutical lobbying. The meta‑analysis from 2023 showed an odds ratio of 1.8, meaning almost double the odds of infection when clarithromycin is used. And yet, guidelines still allow its broad use, as if nothing’s wrong.

Now, consider the vulnerable groups: the elderly, those on PPIs, recent surgery patients, and anyone with a weakened immune system. These are the very people the healthcare establishment tells you to protect, yet we’re feeding them a drug that can sabotage their microbiome. The probiotic story is a comforting myth – sure, Saccharomyces boulardii might shave off a few percentages, but it’s not a license to be reckless.

We need stewardship, not just talk. Reserve clarithromycin only when culture data prove it’s the only effective option. Shorten the course, monitor stool output, and, most importantly, question why a drug that’s only “moderately” risky is being prescribed so liberally. The fight against C. diff isn’t just about antibiotics; it’s about confronting a system that hides the real numbers and lets profit dictate practice. If you want to protect patients, start by demanding transparency, enforce stricter guidelines, and stop normalizing moderate‑risk antibiotics as first‑line therapy. The gut microbiome is not a battlefield for pharmaceutical wars; it’s a delicate ecosystem that deserves better. In short, be vigilant, be skeptical, and demand better stewardship – because the alternative is a silent, growing epidemic of C. diff that no one seems eager to admit.

Sireesh Kumar

December 26, 2025 AT 09:23Look, the numbers speak for themselves – you can’t ignore a 1.2% CDI rate in hospitals. If you’re treating a patient with a clear indication for macrolides, go for it, but make it a short, targeted course. And yes, the probiotic thing isn’t a magic bullet, but it does help balance the flora, especially in high‑risk cases. In the end, it’s about balance – use the right drug for the right patient, monitor closely, and don’t let “standard practice” become a blind‑spot.

Jonathan Harmeling

January 8, 2026 AT 09:00Honestly, prescribing clarithromycin without checking for alternatives feels like a lazy gamble – you’re courting trouble for the patient’s gut ecosystem.

Holly Green

January 21, 2026 AT 08:38Short courses are key – keep it under a week whenever possible.

Ritik Chaurasia

February 3, 2026 AT 08:15From a cultural standpoint, many communities still rely on older antibiotics like amoxicillin‑clavulanate because they trust the lower CDI numbers. Introducing clarithromycin without clear benefit can break that trust, especially when word spreads about gut complications. It’s essential to respect local prescribing habits while educating about the real risks and benefits.

Ben Collins

February 16, 2026 AT 07:53Oh great, another reminder that we need to watch our antibiotic choices – because apparently we’ve all been treating C. diff like a casual cold.