Drug Withdrawal Timeline Calculator

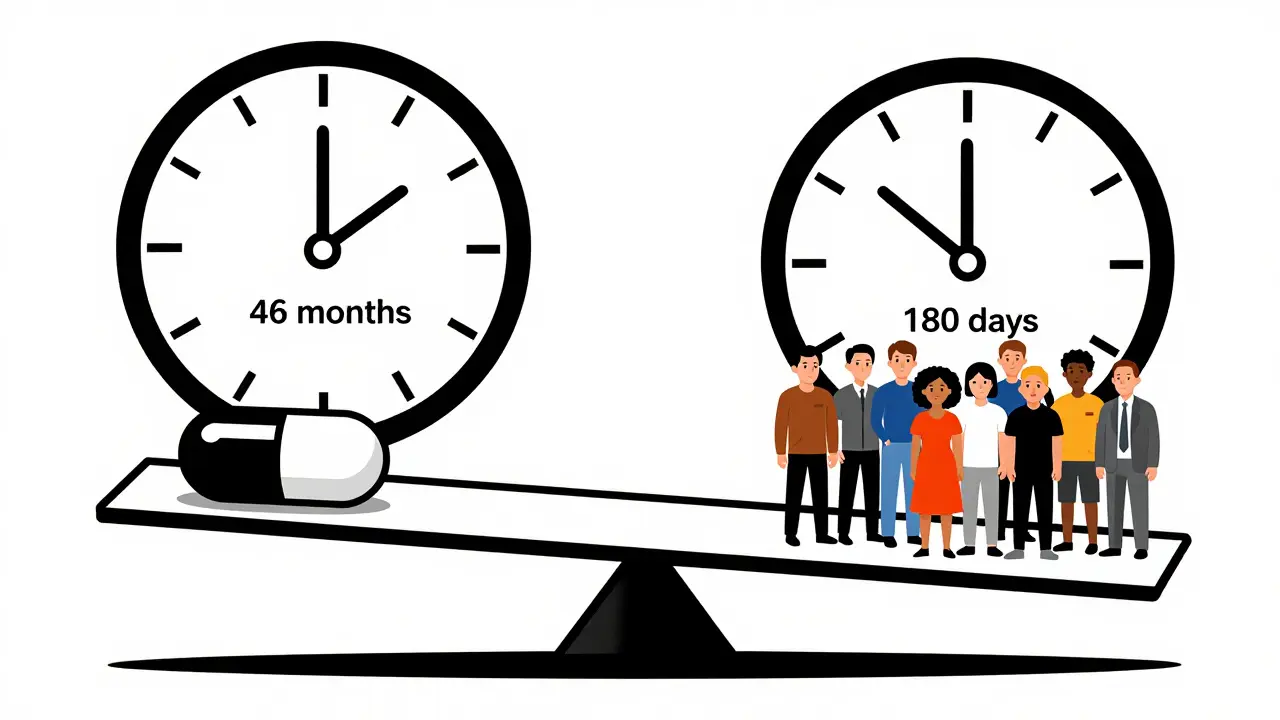

The FDA used to take an average of 46 months to withdraw a drug after evidence showed it didn't work. With the new 2023 law, the process is now streamlined to 180 days (6 months). This tool estimates withdrawal timelines based on your selection.

Withdrawal Timeline Estimate

Select options to see your estimate.

Why Timelines Matter

Before 2023, the average withdrawal timeline was 46 months. During that time, an estimated 150,000 women were given Makena (a drug for preterm birth) that didn't work. The 2023 law now requires the FDA to make a final decision within 180 days of a withdrawal notice.

Drugs approved under the accelerated pathway (like 26% of cancer drugs) often had longer withdrawal timelines because confirmatory trials weren't completed on time. Now with the new law, this timeline is significantly reduced.

Every year, dozens of medications are pulled from shelves-not because they’re outdated, but because they’re dangerous or simply don’t work. This isn’t a glitch in the system. It’s the system working as it should. But the process has been painfully slow, and for too long, patients have been left taking drugs that were later proven to offer no real benefit. The question isn’t just why drugs get pulled. It’s how long it takes, and who pays the price in the meantime.

What Actually Triggers a Drug Recall or Withdrawal?

Not all drug removals are the same. Some are voluntary. Others are forced. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) doesn’t just wake up one day and say, “This drug is gone.” There’s a legal framework behind it, spelled out in the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. The FDA distinguishes between two main types: withdrawals and recalls. A withdrawal happens when the FDA determines a drug is no longer safe or effective. This isn’t about a bad batch or a labeling error. It’s about the drug itself failing its core promise. A recall is usually more limited-like a single lot of pills contaminated in the factory. Withdrawals are systemic. They affect every pill, every prescription, every patient who’s ever taken the drug. The most common reasons? Safety issues (about 60% of cases) and lack of effectiveness (the rest). In oncology, where drugs are often approved fast to help patients with few options, this problem is worst. About 26% of cancer drugs approved under the FDA’s accelerated pathway eventually get pulled. That means nearly one in four of these high-stakes treatments didn’t deliver what they promised.The Accelerated Approval Loophole

The FDA’s accelerated approval program was designed to get life-saving drugs to patients faster. Instead of waiting years for proof that a drug extends life, regulators could approve it based on early signals-like tumor shrinkage or lab results. It made sense. But there was a catch: sponsors had to follow up with confirmatory trials. And for decades, they didn’t always do it on time-or at all. Take Makena. Approved in 2011 to prevent preterm birth, it was based on a small, outdated study. By 2020, a large, rigorous trial showed it didn’t work. But the FDA didn’t pull it until 2022. That’s 1,500 days between proof it failed and the actual withdrawal. During that time, an estimated 150,000 women were given a drug that offered no benefit. And it wasn’t just Makena. Between 2010 and 2020, 12.7% of all accelerated approvals were eventually withdrawn. On average, patients were exposed to these drugs for 4.2 years before they were pulled. The problem wasn’t just the drug. It was the delay. Patients, doctors, and pharmacies kept prescribing and filling prescriptions because the drug was still listed as approved. The system didn’t warn them fast enough.How the FDA Used to Handle Withdrawals (and Why It Failed)

Before 2023, the FDA had no real timeline for pulling drugs. If a drug failed its confirmatory trial, the agency could take years to act. The process was opaque. Sponsors got notice, but there was no pressure to move quickly. The FDA could request meetings, allow appeals, and wait for public comments-all while the drug stayed on the market. The result? A dangerous lag. A 2023 study from the Penn LDI found the FDA took an average of 46 months to withdraw a drug after evidence showed it didn’t work. In some cases, like small cell lung cancer drugs, 41% of eligible patients were still getting treatments that were later proven useless. Doctors weren’t always to blame. Many didn’t know the drug had been flagged. Pharmacists struggled to interpret the FDA’s Orange Book listings, which track approved drugs. A 2022 survey found 63% of pharmacists had trouble understanding whether a drug was still approved. And the FDA’s own audit in 2023 showed only 42% of withdrawal notices included clear guidance on how to transition patients to safer alternatives.

The 2023 Fix: A New Law, A Faster Process

In December 2023, Congress passed the Consolidated Appropriations Act-and with it, a major overhaul of how the FDA handles drug withdrawals. For the first time, the agency got clear, enforceable tools to act fast. Under the new rules, the FDA can now initiate a streamlined withdrawal process if:- The drug sponsor fails to conduct required post-approval studies

- The confirmatory trial doesn’t prove the drug works

- Independent studies show the drug is unsafe or ineffective

- The company promotes the drug with false or misleading claims

What This Means for Patients and Doctors

For patients, this change is personal. One woman on a cancer forum wrote: “I was on [withdrawn drug] for 18 months. My oncologist said it was standard care. Now I know it didn’t help.” That’s not rare. A 2022 study from the American Journal of Managed Care found that 30% of patients on accelerated approval cancer drugs between 2015 and 2020 received treatments later pulled for lack of effectiveness. Doctors are also adapting. Oncology practices now have to build withdrawal response plans. When a drug is pulled, they have an average of 72 hours to switch patients to another treatment. That’s tight. But it’s better than being blindsided. Pharmacists are getting better tools too. The FDA now publishes detailed “Determination of Safety or Effectiveness” notices in the Federal Register. These are clearer than the old Orange Book listings. Still, not everyone is caught up. Many community pharmacies still rely on outdated software that doesn’t flag withdrawn drugs in real time.How the U.S. Compares to the Rest of the World

The U.S. used to be an outlier. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) and Health Canada have long used “conditional approval” systems. These come with built-in deadlines. If the drug doesn’t prove itself, the approval expires automatically. The FDA didn’t have that power. It relied on Postmarketing Required studies (PMRs), which were often ignored or delayed. The 2023 law borrowed from this model. Now, the FDA can tie approval to performance-just like Europe. This shift is more than bureaucratic. It’s ethical. Patients shouldn’t be guinea pigs after a drug is approved. If a drug doesn’t work, it shouldn’t stay on the shelf for years while the paperwork moves slowly.

What’s Next? Real-World Evidence and the Future

The FDA is now testing a new way to catch failing drugs faster: real-world data. In January 2024, it launched a pilot using data from Flatiron Health, which tracks outcomes from thousands of cancer patients in clinics across the U.S. Instead of waiting for a formal trial, the agency can now look at how patients are actually doing on a drug in the real world. Evaluate Pharma predicts that between 2023 and 2027, withdrawal actions will increase by 25%. That’s not because more drugs are bad. It’s because the system is finally working. But there’s still risk. Pharmaceutical groups warn that too-fast withdrawals could scare off innovation. If companies think any early success could lead to a quick pull, they might avoid high-risk areas like rare diseases or aggressive cancers. The FDA says it’s balancing speed with fairness. The new process gives sponsors multiple chances to respond. They can appeal. They can present new data. But the clock is ticking. And for the first time, patients are no longer stuck waiting for the system to catch up.What You Should Know If You’re Taking a Recently Approved Drug

If you’re on a drug approved under accelerated approval-especially for cancer, rare diseases, or neurological conditions-ask your doctor this: “Has this been confirmed to work in a large trial?” If it hasn’t, you’re part of the ongoing study. That’s not necessarily bad. But you should know the risk. Check the FDA’s website for the latest withdrawal notices. They’re posted in the Federal Register and on the FDA’s Drug Withdrawals page. You don’t need to be a scientist to read them. Look for phrases like “withdrawn due to failure to verify clinical benefit” or “no longer considered safe.” Don’t panic if your drug gets pulled. That’s not a failure of the drug-it’s a success of the system. The goal isn’t to keep drugs on the market forever. It’s to make sure only the ones that truly help stay there.Final Thoughts: A System That’s Learning

Drug withdrawals used to be rare events. Now, they’re inevitable-and necessary. The system is no longer broken. It’s evolving. The Makena case was a wake-up call. The 2023 law was the response. And the patients who waited too long? They’re why the change happened. This isn’t about punishing companies. It’s about protecting people. Every day a drug stays on the market after it’s proven ineffective, someone is being treated with a placebo dressed up as medicine. The new rules don’t make that happen anymore. They make sure it ends faster.What’s the difference between a drug recall and a withdrawal?

A recall is usually for a specific batch of medication that’s contaminated, mislabeled, or defective. A withdrawal means the FDA has determined the drug itself is unsafe or ineffective-and it’s pulled from the market entirely. Withdrawals affect all versions of the drug, everywhere.

How long does it take for the FDA to pull a drug now?

Under the 2023 law, the FDA must make a final decision within 180 days of issuing a notice of proposed withdrawal. Before that, the average was 46 months. The goal is to reduce that to under 12 months for drugs approved after the law passed.

Are all withdrawn drugs dangerous?

Not always. Some are pulled because they don’t work-not because they cause harm. For example, Makena didn’t cause serious side effects, but it didn’t prevent preterm birth either. In those cases, the risk is wasted treatment and false hope, not poisoning.

Can a drug be pulled even if it’s still being sold by other countries?

Yes. The FDA’s decision is based on U.S. data and patient safety standards. A drug approved in Canada or the EU might still be pulled in the U.S. if the evidence shows it doesn’t benefit American patients-or if the risks outweigh the benefits here.

How can I find out if my medication has been withdrawn?

Check the FDA’s official Drug Withdrawals page or search the Federal Register for “Determination of Safety or Effectiveness.” Your pharmacist can also check the FDA’s Orange Book, but newer systems now flag withdrawals in real time. Always ask your doctor if you’re unsure.

Do drug withdrawals mean the FDA made a mistake approving them?

Not always. Accelerated approval was meant to get drugs to patients with serious illnesses faster, based on early signs of benefit. The problem wasn’t the approval-it was the failure to confirm benefit quickly enough. The new system fixes that gap. It’s not about blame. It’s about getting better at protecting people.

Alana Koerts

December 18, 2025 AT 14:24So the FDA finally got a spine after 15 years of letting pharma laugh at them? Good. Took long enough. Makena was a joke. 150k women given placebo pills dressed as medicine. And the worst part? Doctors didn't even know it was suspect. System was broken. Now it's just slow.

Dikshita Mehta

December 20, 2025 AT 11:18This is actually one of the most well-explained pieces on drug regulation I've read. The distinction between recall and withdrawal is critical, and the 2023 timeline changes are a major step forward. Real-world data from Flatiron Health could be game-changing-finally moving beyond surrogate endpoints. Hope this becomes global standard.

pascal pantel

December 20, 2025 AT 11:48Accelerated approval was never meant to be a backdoor for pharma to skip Phase 3. It's a regulatory shell game. They get the revenue stream, patients get hope, regulators get press releases. The 46-month lag wasn't bureaucracy-it was collusion. And now they want applause for cutting it to 180 days? That's not reform. That's damage control. Still not fast enough. If a drug fails confirmatory trials, pull it the day the data lands. Not after a meeting. Not after an appeal. Just pull it.

Guillaume VanderEst

December 22, 2025 AT 02:34I had a friend on one of those accelerated cancer drugs. Spent $80k out of pocket. Got zero benefit. Then one day, poof-gone from the pharmacy system. No warning. No transition plan. Just ‘sorry, your treatment’s invalid.’ That’s not healthcare. That’s corporate roulette. And now the FDA’s got a 12-month deadline? Congrats. You just made the system marginally less cruel.

Nina Stacey

December 23, 2025 AT 05:31Okay so I just found out my mom’s been on this drug for two years and it was pulled last year?? I’m so mad but also kinda relieved? Like wow we didn’t know and now we know and we switched but I feel like this happens way too often and why do we have to be the ones to dig through federal register when the doctor should be telling us?? Also I think the FDA is trying but the system is still a mess and honestly I just want to know if my meds are legit without having to become a pharmacist

Dominic Suyo

December 25, 2025 AT 00:07Let’s be real-this isn’t about patient safety. It’s about liability. Pharma pays regulators in lobbying cash, not in ethics. The 2023 law? A PR move. The real test? Will they pull a drug from a company that donates to the FDA commissioner’s alma mater? Doubt it. And don’t give me that ‘it’s evolving’ crap. We’ve been told that since 2008. Still waiting for the revolution.

Kevin Motta Top

December 25, 2025 AT 18:20Canada’s been doing this for years. Conditional approval, automatic expiry if data isn’t delivered. Simple. Clean. No drama. The U.S. finally caught up. Good. Now let’s make sure it sticks.

Alisa Silvia Bila

December 26, 2025 AT 22:57My oncologist just told me the drug I’m on was approved under accelerated pathway. She said she’s been watching the confirmatory trial results. We’re not panicking, just staying informed. Honestly, I’m glad the system’s finally catching up. It’s scary knowing you’re part of a real-world experiment, but at least now there’s a timeline. That’s more than we had before.

Erica Vest

December 28, 2025 AT 01:09The FDA’s new 180-day deadline is a start, but the real win is transparency. The ‘Determination of Safety or Effectiveness’ notices are finally readable. No more decoding the Orange Book. Pharmacists can actually use them. This isn’t perfect-but it’s the first time the system speaks English to patients and providers. Progress, not perfection.