When a pharmacist hands you a bottle of compounded medication, it doesn’t come with a manufacturer’s expiration date like the pills you get at a regular pharmacy. Instead, it has a beyond-use date - or BUD. This isn’t just a label. It’s a safety deadline. Get it wrong, and you risk taking a drug that’s broken down, contaminated, or no longer effective. And that’s not theoretical. In 2021, over 1,200 compounded sterile products were recalled because someone assigned a BUD that was too long. The FDA stepped in. Hospitals shut down compounding labs. Patients got sick. This isn’t about being overly cautious. It’s about understanding what that date really means - and why you can’t treat it like a regular expiration date.

What Exactly Is a Beyond-Use Date?

A beyond-use date is the last day a compounded medication is safe and effective to use. It’s calculated from the day the medication was mixed, not the day you picked it up. Unlike FDA-approved drugs, which undergo years of stability testing before hitting shelves, compounded medications are made one batch at a time - often for a single patient. That means there’s no large-scale data to rely on. The BUD is the pharmacist’s best scientific guess, based on rules, literature, and sometimes direct testing. The U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP) sets the standard. Specifically, USP Chapter <797> governs how sterile compounded medications are handled and dated. The FDA backs this up. If a pharmacy assigns a BUD that doesn’t follow USP guidelines, they’re breaking federal rules. The goal? Prevent patients from getting drugs that have degraded chemically, separated physically, or grown harmful bacteria.Why Can’t You Just Use the Expiration Date on the Original Bottle?

It’s a common mistake. You see a vial of epinephrine with an expiration date two years out. You think, “Great, I can use that for two years in my compounded solution.” Wrong. That expiration date applies only to the drug in its original, factory-sealed container, under factory-controlled conditions. Once you open it, mix it with other ingredients, or put it in a different container - like a syringe or an IV bag - everything changes. A 2021 study in the International Journal of Pharmaceutical Compounding showed that excipients - the non-active ingredients like preservatives or stabilizers - can change how fast the main drug breaks down. In one case, a simple change in pH made a medication degrade 3.7 times faster than its commercial version. That’s not a small difference. It’s the difference between a safe dose and a useless, or even dangerous, one. And containers matter. Glass vials behave differently than plastic bags. Syringes aren’t designed for long-term storage. Yet, a 2022 survey found that over 40% of retail compounding pharmacies still used syringe-based BUDs based on vial stability data - even though the FDA has explicitly warned that syringes aren’t approved storage devices. That’s like using a paper cup to store gasoline and assuming it won’t leak.How Pharmacists Actually Determine a BUD

Assigning a BUD isn’t guesswork. It’s a five-step process, backed by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP):- Identify every ingredient - including concentrations, sources, and any additives.

- Classify the risk level - low, medium, or high - based on how sterile the process was and whether it’s water-based. Water invites bacteria. That’s the biggest threat.

- Check manufacturer labels - sometimes the original drug maker has stability data for diluted or mixed forms.

- Look up validated literature - databases like the International Journal of Pharmaceutical Compounding’s Stability Database have over 14,700 tested formulations. But only about 30% of pharmacists use them regularly.

- Apply professional judgment - if the data is thin, err on the side of caution. Don’t stretch it.

What Are the Rules for BUD Lengths?

USP <797> sets clear limits based on risk level and storage:- Low-risk (sterile, no water, minimal handling): Up to 48 hours at room temperature, or 14 days if refrigerated (30 days if tested).

- Medium-risk (water-based, some manipulation): Up to 30 hours at room temperature, or 7 days refrigerated.

- High-risk (complex mixes, non-sterile ingredients, multiple steps): Maximum 24 hours at room temperature, or 48 hours refrigerated - and only if tested.

Why Do So Many Pharmacies Get It Wrong?

The biggest issue? Lack of training and resources. A 2023 survey found that nearly two-thirds of compounding pharmacists struggle to find published data matching their exact formula. Many don’t have access to labs for testing. Some don’t even know where to look. There’s also pressure. If a patient needs a medication tomorrow, and the only way to get it is to stretch the BUD, some pharmacists do it. They think, “It’s probably fine.” But “probably fine” isn’t good enough. A 2022 analysis in the Journal of the American Pharmacists Association found that 12.7% of medication errors involving compounded drugs were tied to incorrect BUDs. Even worse, some pharmacies use outdated guidelines. The 2023 revision of USP <797> increased refrigerated BUDs for water-based formulations from 14 to 30 days - but only if proper testing is done. Many pharmacies are still using the old rules. That’s a ticking time bomb.

What Should You Do as a Patient?

You don’t need to be a chemist. But you do need to ask questions.- Ask for the BUD - and make sure it’s written on the label, not just in a note.

- Check the storage instructions - Is it refrigerated? Keep it cold. If it says “room temperature,” don’t leave it in a hot car.

- Don’t use it after the date - Even if it looks fine. Degradation isn’t always visible. A cloudy solution? Throw it out. A strange smell? Throw it out. A date passed? Throw it out.

- Ask if it was tested - If the BUD is longer than a few days, it should be backed by lab data. Most small pharmacies can’t do that. That’s okay - just know the BUD will be short.

What’s Changing in the Future?

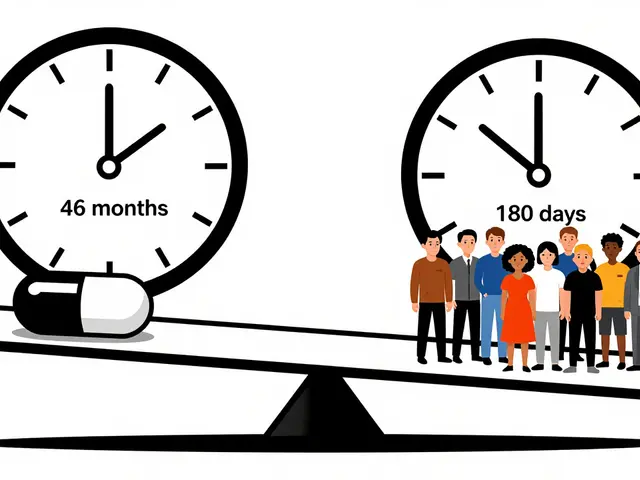

The compounding industry is growing. By 2030, nearly one in five prescriptions could be compounded - up from less than one in ten today. That means more people will rely on these medications. And that means more pressure to get BUDs right. New tools are emerging. SmartBUD systems, which monitor real-time stability in storage units, are already cutting errors by nearly half in pilot programs. The FDA is pushing for stricter rules. USP’s 2024 draft proposes requiring direct testing for any BUD longer than 30 days. That will force more pharmacies to invest in labs - or stop making long-dated products. The bottom line? BUDs aren’t arbitrary. They’re science. And science doesn’t bend for convenience. The longer the BUD, the more proof you need. The more complex the formula, the shorter the window. And if you’re not sure - don’t use it.What Happens If You Use a Compounded Medication Past Its BUD?

You might not feel anything right away. But here’s what’s happening inside that vial:- Chemical breakdown - The active ingredient loses potency. You might think you’re getting a full dose, but you’re getting half - or less.

- Physical separation - Oils and water can separate. Injecting that could cause blockages or embolisms.

- Microbial growth - Bacteria, fungi, mold. These can cause serious infections, especially in IVs or injections. In 2021, a single pharmacy’s BUD error led to 11 cases of bloodstream infections. Two patients died.

Is a beyond-use date the same as an expiration date?

No. An expiration date is assigned by the manufacturer after years of FDA-approved stability testing on a standardized product. A beyond-use date (BUD) is assigned by the compounding pharmacist based on scientific guidelines, literature, or direct testing - and applies only to that specific batch. BUDs are usually much shorter and are calculated from the day the medication was mixed, not the day it was made.

Can I extend a beyond-use date if the medication looks fine?

Never. Physical appearance - clarity, color, or smell - is not a reliable indicator of safety or potency. Chemical degradation and microbial contamination can occur without visible signs. Extending a BUD without proper testing violates USP and FDA guidelines and puts patients at serious risk.

Why do some compounded medications have longer BUDs than others?

BUD length depends on risk level, storage conditions, and formulation. Low-risk, non-water-based preparations (like some topical creams) can have longer BUDs - up to 48 hours at room temperature or 14-30 days refrigerated if tested. High-risk, water-based injectables are limited to 24 hours or less. The more complex the mix, the shorter the BUD.

Do I need to refrigerate my compounded medication?

Only if the label says so. Refrigeration slows chemical breakdown and bacterial growth, especially in water-based formulas. But not all compounded meds need it. Some are stable at room temperature for a few hours. Always follow the storage instructions on the label. If you’re unsure, ask the pharmacy.

What should I do if my pharmacy gave me a BUD longer than 30 days?

Ask how they determined it. If they say it’s based on literature or manufacturer data alone, be cautious. Under current USP guidelines, BUDs longer than 30 days require direct stability testing. If they can’t show proof of testing, consider getting the medication from a different pharmacy - or ask your doctor if an FDA-approved alternative exists.

Olivia Portier

December 8, 2025 AT 17:27Okay but can we just take a second to appreciate how wild it is that we’re trusting our health to someone’s best guess? Like, I get that pharmacies are stretched thin, but if your meds are sitting in a syringe for 10 days because ‘it looks fine,’ we’ve got bigger problems than just bad labeling. This isn’t DIY kombucha - lives are on the line.

Jennifer Blandford

December 8, 2025 AT 21:37OMG I had a compounded pain cream last year and the pharmacist wrote the BUD on a sticky note and stuck it on the bottle. I almost threw it out because I thought it was trash. Then I realized - ohhh, that’s the deadline. 😳 I called them and they were like ‘yeah, we don’t have a printer.’ Like… why are we still doing this? The tech exists. The rules exist. We’re just lazy.

Raja Herbal

December 9, 2025 AT 23:55So let me get this straight - you’re telling me that in a country that can send rovers to Mars, we can’t standardize a damn drug label? I mean, we’ve got apps that track your coffee intake, but if you need a compounded antibiotic, you’re basically playing Russian roulette with your immune system. Thanks, capitalism.

Rich Paul

December 11, 2025 AT 17:39Look, USP 797 is a mess. The whole framework is outdated. HPLC testing? Most small pharmacies can’t afford it. You don’t need to test every batch - you need risk-based predictive modeling. We’ve got ML models that can predict degradation with 92% accuracy using just ingredient ratios and storage logs. But nooo, we’re still using paper logs from 2008. The system is broken. Fix the infrastructure, not the labels.

Simran Chettiar

December 12, 2025 AT 20:19It’s fascinating, really, how we’ve constructed this entire edifice of medical trust upon the fragile scaffolding of human judgment - a system where a single pharmacist, often overworked and under-resourced, becomes the sole arbiter of life and death for a patient who has no way to verify the science behind a date scribbled on a plastic vial. We treat pharmaceuticals like sacred texts, yet deny them the institutional rigor that would make them truly reliable. The beyond-use date is not a date - it’s a confession of systemic failure masked as protocol. And yet, we nod politely, take our little bottle, and go home, trusting that the gods of pharmacology have smiled upon us today. How quaint. How tragic. How utterly, terrifyingly human.

Tiffany Sowby

December 13, 2025 AT 15:26Ugh. Another ‘pharmacist is the hero’ story. Newsflash: most compounding pharmacies are run by people who barely passed their pharmacology class. I’ve seen BUDs written in Sharpie on duct tape. And you want me to trust that? I’d rather take a pill made in China than some ‘custom blend’ from a basement lab with no air filtration. #AmericaFirst #JustBuyTheFDAApprovedOne

Ryan Brady

December 15, 2025 AT 07:42LOL at people stressing over BUDs. I’ve used stuff 3 weeks past the date and felt fine. My cousin took a compounded steroid and lived. It’s not like it’s poison. Chill. 🤷♂️

Brianna Black

December 15, 2025 AT 15:02My grandma’s compounded heart med had a 14-day refrigerated BUD - but the pharmacy gave her a 30-day one because ‘she’s old and doesn’t come in often.’ She didn’t know the difference. She took it 22 days later. Got a nasty infection. Hospitalized for a week. The pharmacy said ‘it was just a little over.’ Just a little? That’s not a mistake. That’s negligence. And if you’re a patient, you deserve better than ‘just a little.’