Why do some people struggle to lose weight even when they eat less and move more? It’s not laziness. It’s not willpower. At the core of obesity is a broken system - one that controls hunger, fullness, and how your body burns energy. This isn’t just about calories in versus calories out. It’s about biology gone wrong.

The Brain’s Hunger Switches

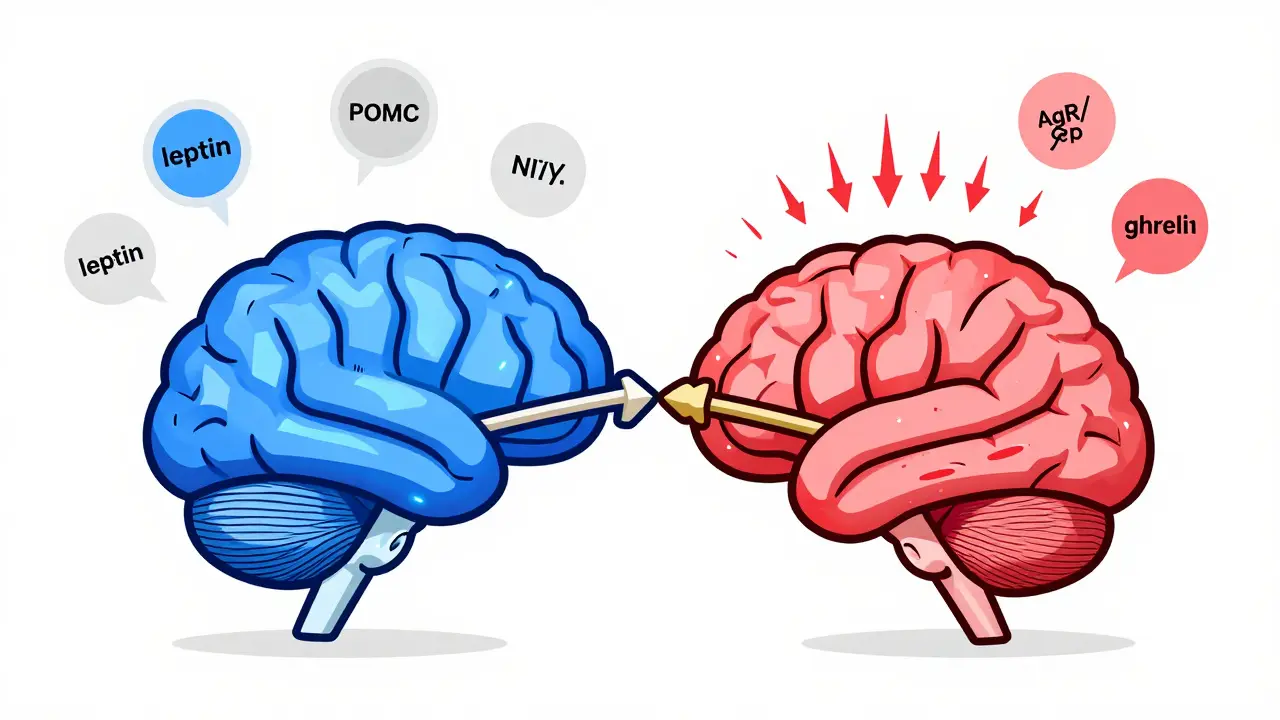

Your hypothalamus, a tiny region deep in your brain, acts like the control center for your appetite. Inside it, two groups of neurons are locked in a constant tug-of-war. One group, called POMC neurons, tells you to stop eating. They release a signal called alpha-MSH, which activates receptors that make you feel full. In lab studies, turning these neurons on reduces food intake by 25% to 40%. The other group, NPY and AgRP neurons, screams for more food. Activate them with light in a mouse experiment, and the animal eats 300% to 500% more in minutes. These neurons don’t work alone. They listen to signals from your fat cells, stomach, and pancreas. Leptin, a hormone made by fat tissue, is supposed to say, “You’ve got enough stored - stop eating.” In lean people, leptin levels sit between 5 and 15 ng/mL. In obesity, those levels jump to 30-60 ng/mL. But here’s the twist: the brain stops listening. That’s called leptin resistance. It’s not that you don’t have enough leptin - you have too much, and your brain ignores it. This is the #1 problem in common obesity, not a lack of the hormone.Insulin, Ghrelin, and the Hunger Cycle

Insulin, the hormone that moves sugar into your cells, also tells your brain to cut back on eating. When you fast, insulin dips to 5-15 μU/mL. After a meal, it spikes to 50-100 μU/mL - and that’s supposed to help you feel satisfied. But in people with insulin resistance - common in obesity - the brain doesn’t respond properly. So even with high insulin, hunger doesn’t turn off. Then there’s ghrelin, the only known hunger hormone. It rises before meals, peaking at 800-1000 pg/mL, and directly fires up those NPY/AgRP neurons. In obesity, ghrelin doesn’t drop as it should after eating. That means you feel hungry sooner, even if you just ate. Some people with severe obesity have ghrelin levels that stay stubbornly high, making it nearly impossible to feel full.How Fat Cells Rewire Your Brain

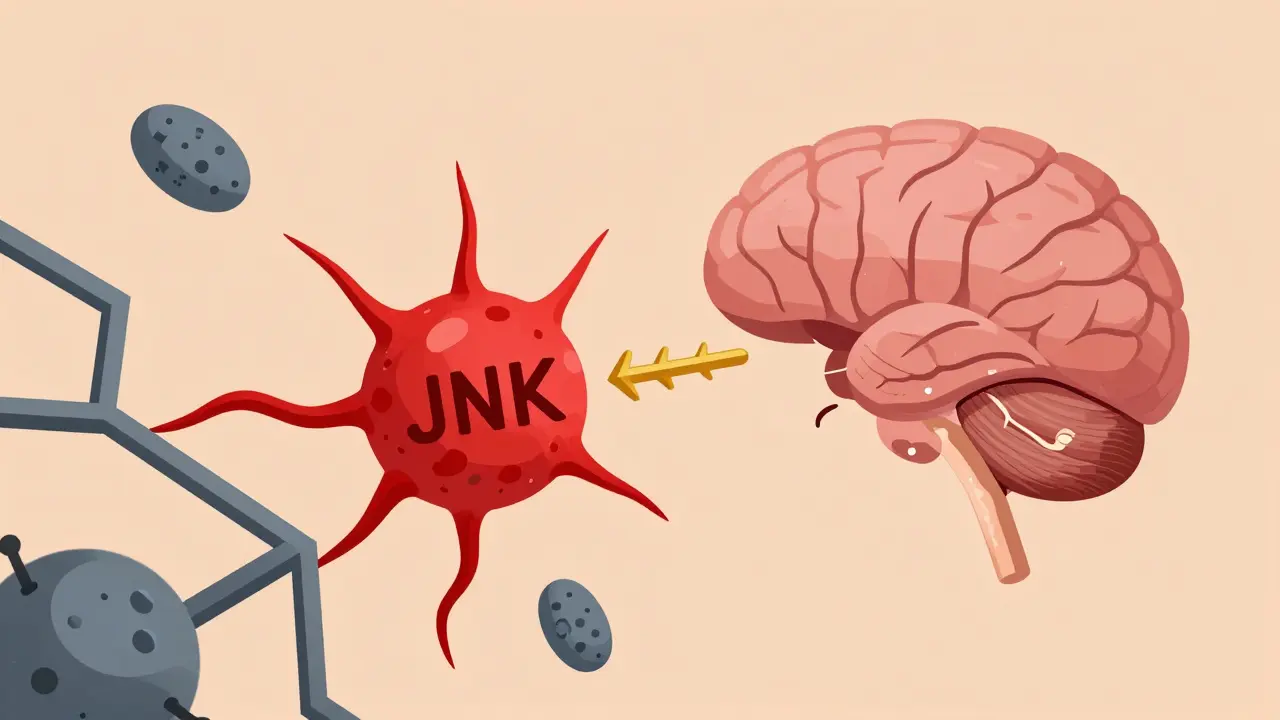

Fat isn’t just storage. It’s an active organ that talks to your brain. In obesity, fat tissue releases inflammatory signals that mess with the brain’s signaling pathways. One key player is JNK, a protein that gets turned on by inflammation. When JNK is active, it blocks leptin from working - even if leptin levels are sky-high. Another pathway, PI3K/AKT, is where leptin and insulin meet. If this pathway is blocked - say, by a genetic mutation or chronic inflammation - leptin can’t tell your brain to stop eating. Experiments show that shutting down PI3K in the brain makes leptin useless. The signal is there, but the message never gets through. Even the mTOR system, which helps regulate metabolism and cell growth, gets thrown off. When mTOR is overstimulated in obesity, it contributes to appetite dysregulation. On the flip side, stimulating mTOR in lab animals reduces food intake by 25%. This shows how finely tuned the system is - and how easily it breaks.

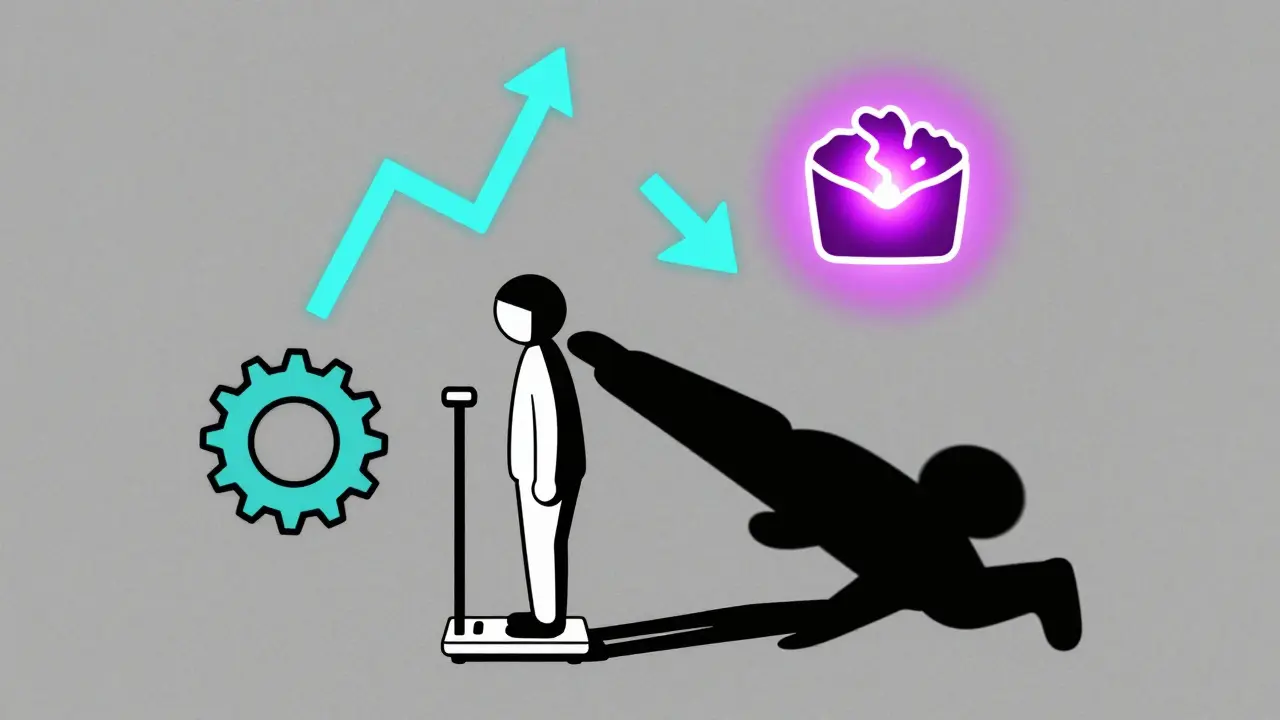

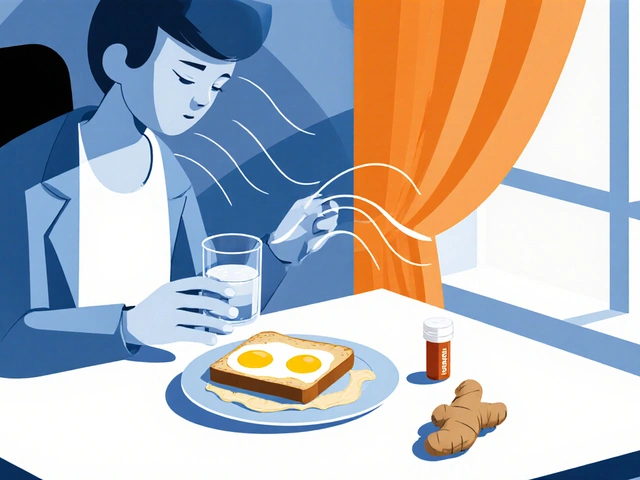

Why Diets Often Fail

When you lose weight, your body fights back. Leptin levels drop. Ghrelin rises. Your brain thinks you’re starving. This isn’t psychological - it’s biological. Your body is trying to return to its old, heavier weight. That’s why most people regain lost weight within a year. The system resets to defend the higher fat mass. Add to that the fact that modern diets are packed with ultra-processed foods - high in sugar, fat, and salt - and you’ve got a perfect storm. These foods hijack the brain’s reward system. The melanocortin pathway, which normally limits overeating, gets overwhelmed by the pleasure of eating highly palatable food. Studies show that when people with genetic defects in this pathway eat junk food, their overeating gets dramatically worse. It’s not just biology - it’s biology + environment.Other Hormones That Matter

Pancreatic polypeptide (PP), released after meals, slows digestion and reduces hunger. But in 60% of people with diet-induced obesity, PP levels are abnormally low - meaning this natural “stop eating” signal is missing. In Prader-Willi syndrome, a rare genetic disorder that causes extreme hunger, PP levels are so low they’re almost undetectable. Estrogen also plays a role. After menopause, women often gain weight around the belly. That’s because estrogen helps regulate energy balance. When estrogen drops, food intake increases by 12-15%, and energy expenditure drops. Mouse studies show that removing estrogen receptors leads to 25% more eating and 30% less calorie burning. Even sleep-related hormones are involved. Orexin, which helps keep you awake and alert, is reduced by 40% in obese individuals. But in night-eating syndrome, orexin spikes at the wrong times, driving midnight snacking. People with narcolepsy - who have low orexin - are two to three times more likely to be obese.

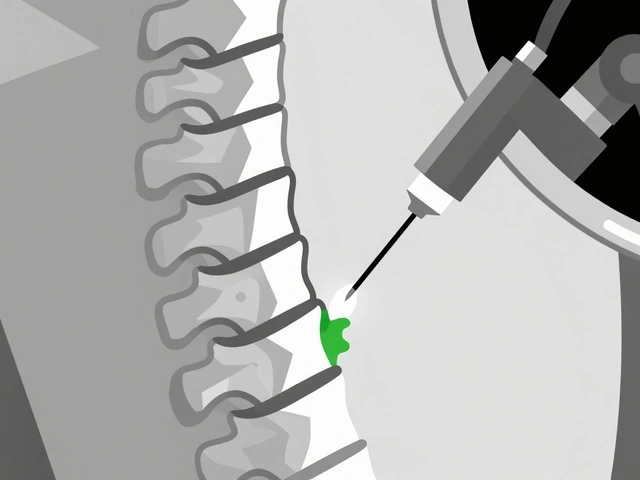

What Treatments Actually Work

New drugs are finally targeting these broken pathways. Setmelanotide, a drug that activates the melanocortin-4 receptor, helps people with rare genetic defects in POMC or leptin receptors lose 15-25% of their body weight. It works because it bypasses the broken leptin signal and directly turns on the “stop eating” switch. Semaglutide, originally a diabetes drug, mimics GLP-1 - a gut hormone that slows digestion and reduces appetite. In clinical trials, people lost an average of 15% of their body weight. It doesn’t just suppress hunger - it makes food less rewarding. You still eat, but you don’t crave it as much. The biggest breakthrough came in 2022, when scientists found a group of neurons next to the hunger and fullness cells that, when activated, shut down eating within two minutes. This opens the door to new drugs that could turn off hunger faster and more precisely than ever before.The Bigger Picture

Obesity affects 42.4% of U.S. adults and nearly 13% of the global population. It’s linked to 2.8 million deaths a year and costs the U.S. healthcare system $173 billion annually. Treating it as a personal failure ignores the science. This is a chronic disease of the brain and metabolism - not a lack of discipline. The good news? We now understand the mechanisms. We know how leptin resistance, insulin miscommunication, and hormonal imbalances drive overeating. We have drugs that target these pathways. The challenge now is making these treatments accessible and combining them with lifestyle support - not replacing it. This isn’t about willpower. It’s about fixing a broken system. And for the first time, we’re starting to know how to fix it.Is obesity caused by eating too much?

It’s not that simple. While eating more than your body needs leads to weight gain, the real issue is why your body drives you to eat more. Hormones like leptin and ghrelin, brain circuits, and metabolic changes make you feel hungrier and less full - even when you’re not lacking calories. Most people with obesity don’t overeat because they lack willpower. Their biology is pushing them to eat more.

Why doesn’t losing weight fix the problem?

When you lose weight, your body reacts like it’s in famine. Leptin levels drop, ghrelin rises, and your metabolism slows down. Your brain tries to restore your previous weight - often the highest weight you’ve ever been. This is a survival mechanism. That’s why most people regain weight, even after years of dieting. The system hasn’t reset; it’s still defending the higher fat mass.

Can genetics cause obesity?

Yes - but rarely. Less than 50 cases worldwide are due to single-gene mutations like leptin deficiency. However, most people carry genetic variations that make them more sensitive to environmental triggers - like high-calorie foods or stress. These genes don’t cause obesity directly, but they make it much easier to develop when combined with modern diets and sedentary lifestyles.

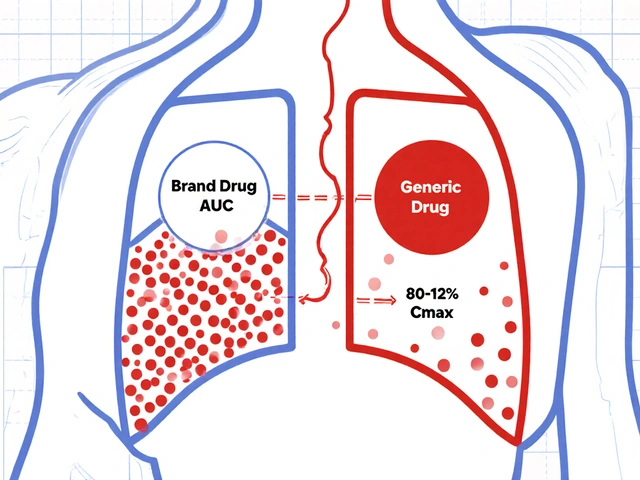

Do obesity drugs just suppress appetite?

They do more than that. Drugs like semaglutide and setmelanotide don’t just make you feel full. They reduce the reward you get from food, slow stomach emptying, and improve how your body uses energy. Some even help your brain relearn normal hunger signals over time. They’re not magic pills - they work best when paired with support for healthy eating and movement.

Is leptin a good weight-loss supplement?

No. Most people with obesity already have high leptin levels - they’re resistant to it. Taking extra leptin won’t help. In fact, clinical trials showed it has no effect on weight loss in common obesity. Leptin therapy only works in the extremely rare cases where someone has a true leptin deficiency - fewer than 50 people ever diagnosed.

Can exercise fix metabolic dysfunction in obesity?

Exercise helps - but not in the way most people think. It doesn’t burn enough calories to cause major weight loss on its own. What it does is improve insulin sensitivity, reduce inflammation, and help the brain respond better to leptin. It doesn’t reverse obesity alone, but it makes other treatments - like medication or diet changes - work better.

Erika Putri Aldana

December 20, 2025 AT 19:18This is why I stopped counting calories lol 😩 My body just won't listen, no matter how hard I try. It's like my brain's on a different planet.

Dan Adkins

December 21, 2025 AT 04:25While the neuroendocrine mechanisms elucidated herein are indeed compelling, one must not overlook the epigenetic modulations induced by prolonged exposure to obesogenic environments. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysregulation, coupled with adipose tissue-derived cytokine overexpression, constitutes a pathophysiological cascade that transcends mere caloric imbalance. It is imperative to reframe public health discourse away from moralistic frameworks toward a biologically grounded paradigm.

Adrian Thompson

December 22, 2025 AT 13:20They don't want you to know this, but Big Pharma and the USDA are in bed together. These 'drugs' are just a cover to sell you more junk. The real cause? Glyphosate in your food. It fries your leptin receptors. They don't tell you because they profit off your sickness. Google 'leptin glyphosate study' - they buried it.

Grace Rehman

December 23, 2025 AT 21:13So we've got a brain that's been hijacked by sugar, salt, and corporate marketing... and now we're supposed to fix it with a pill? Interesting. We've spent decades telling people to 'eat less, move more' while the food industry designed products to override every biological brake we have. Now we're surprised it broke? The real miracle isn't the drug - it's that anyone still has a functioning appetite at all.

Southern NH Pagan Pride

December 25, 2025 AT 10:22leptin resistance is real but what about the 5g of aspartame in your diet coke? it confuses the hypothalamus and makes you crave carbs. i read this on a forum and the science checks out. also the government puts fluoride in the water to make us sleepy so we eat more. its all connected

Orlando Marquez Jr

December 26, 2025 AT 06:53As a physician practicing in a community with high obesity prevalence, I can attest to the profound disconnect between clinical understanding and public perception. The stigma attached to weight is not merely social - it is institutional. When patients are told they lack discipline, they disengage from care. This research offers not only biological insight but a moral imperative: treat obesity as medicine, not morality.

Jackie Be

December 26, 2025 AT 16:36OMG I finally get it why I crave midnight pizza so bad 😭 its not me its my orexin being messed up!! I just started walking after dinner and its already helping my brain feel less hungry at night!! THANK YOU FOR THIS I FEEL SEEN

John Hay

December 28, 2025 AT 09:26I've been on semaglutide for 6 months. Lost 22 lbs. Not because I'm strong - because my brain finally stopped screaming at me to eat. I still eat junk sometimes. But now I don't need it. The drug didn't change me. It just let my body be itself again.