When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you might wonder: is this really the same as the brand-name drug? The answer lies in something called the 80-125% rule-a quiet but powerful standard that ensures generic medications work just like their brand-name counterparts. It’s not about how much active ingredient is in the pill. It’s not about taste, color, or price. It’s about what happens inside your body after you swallow it.

What the 80-125% Rule Actually Means

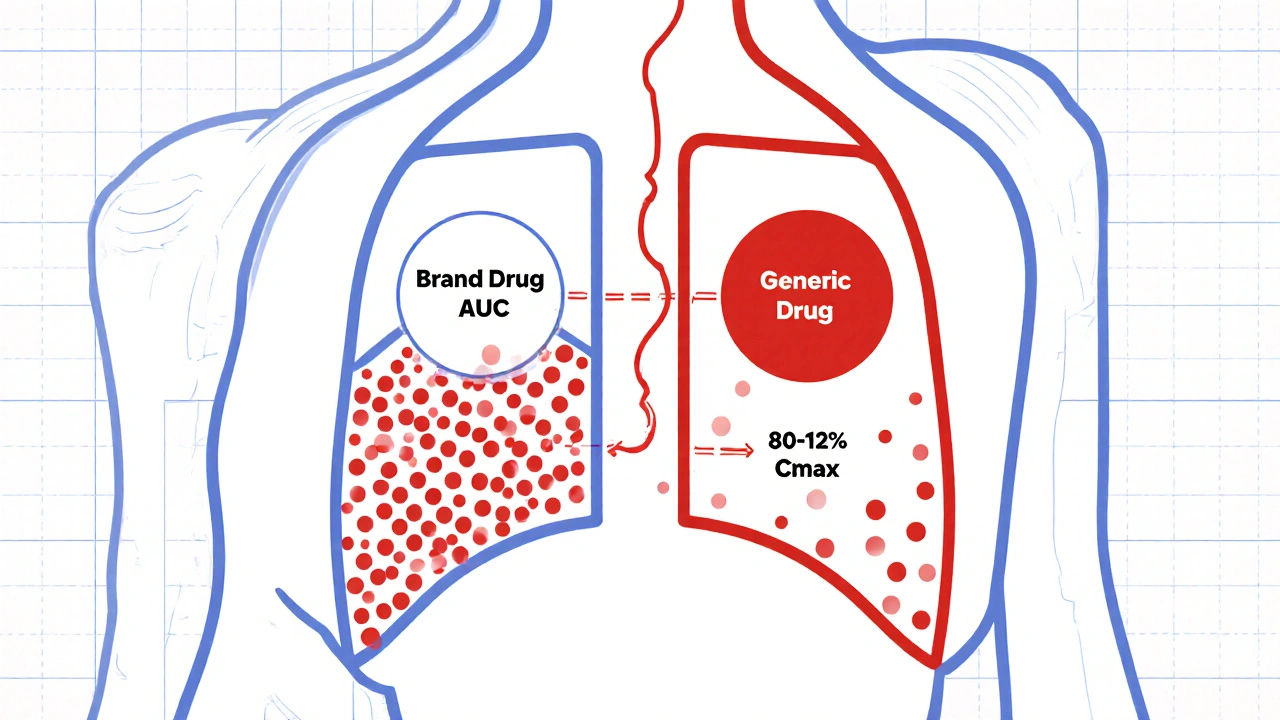

The 80-125% rule is a statistical benchmark used by regulators like the FDA, EMA, and WHO to decide if a generic drug is bioequivalent to the original. Bioequivalence means the generic drug delivers the same amount of active ingredient to your bloodstream at roughly the same speed as the brand-name version. That’s it. No more, no less.

Here’s the catch: it’s not a 20% margin of error in the pill’s dosage. Many people think a generic can contain only 80% of the active ingredient. That’s wrong. Generic pills must contain 95-105% of the labeled amount-same as brand drugs. The 80-125% range applies to the measured exposure in clinical studies, not the amount of drug in the tablet.

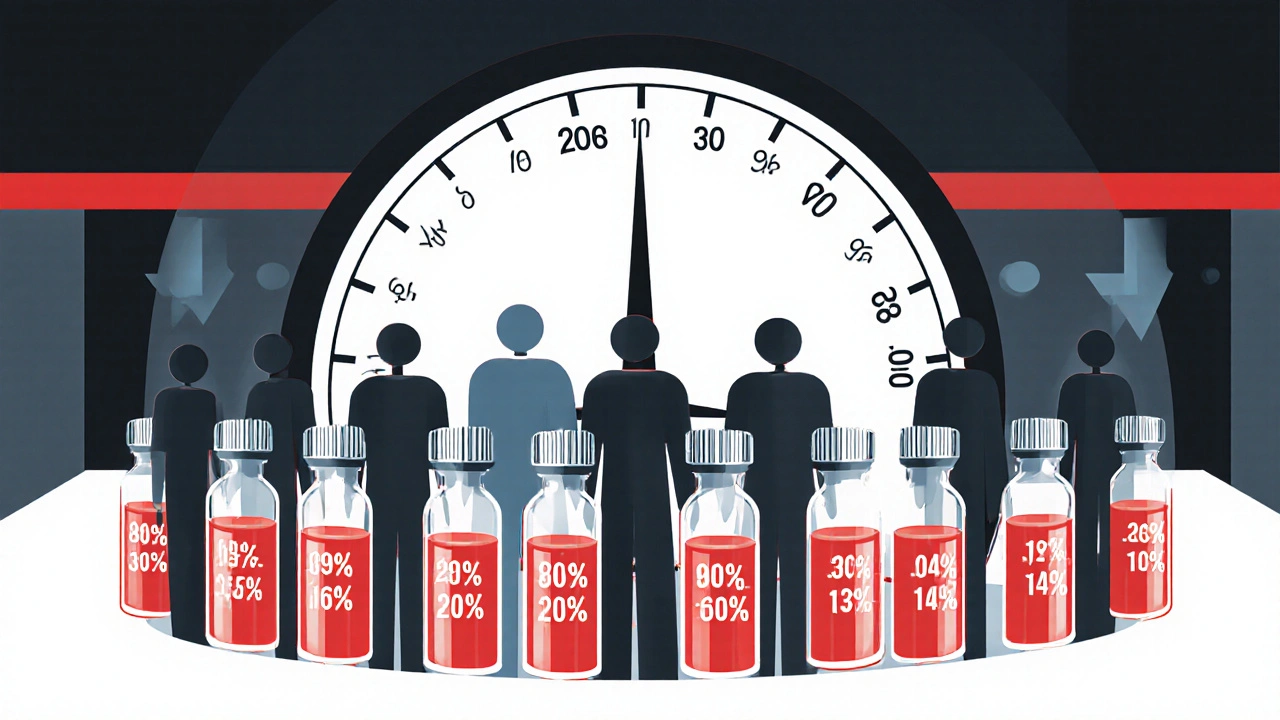

Researchers give volunteers both the brand and generic versions in controlled studies. They measure two key numbers: AUC (how much drug enters your system over time) and Cmax (how fast it gets there). These values are log-transformed because drug levels in blood don’t follow a normal curve-they’re skewed. Then they calculate the 90% confidence interval of the ratio between the generic and brand drug’s geometric means. If that entire interval falls between 80% and 125%, the drugs are considered bioequivalent.

Why 90% confidence interval? Because it allows for a 5% chance of error on each end-totaling 10%. That’s stricter than it sounds. It means there’s a 90% probability the true difference between the two drugs is within that 20% range. This isn’t about statistical significance in the traditional sense. It’s about clinical safety.

Why This Rule Exists

Before the 80-125% rule, regulators used looser standards. In the 1970s, some agencies allowed ±20% differences on the original scale. But that didn’t account for how drugs behave in the body. A 20% difference in absorption could mean a 40% difference in exposure if you didn’t use logarithmic scaling. The switch to the 80-125% range on the log scale fixed that.

The change came after the 1986 FDA Bioequivalence Hearing. Experts reviewed decades of data and concluded: differences under 20% in AUC and Cmax are unlikely to cause real-world problems in patients. That became the new standard. It wasn’t based on randomized trials comparing clinical outcomes-it was based on expert judgment, pharmacokinetic logic, and decades of post-market safety data.

And it worked. Since 1984, over 14,000 generic drugs have been approved in the U.S. alone. Today, 90% of prescriptions are filled with generics. Yet they make up only 23% of total drug spending. That’s billions saved every year-all because this rule lets manufacturers skip expensive clinical trials for every single generic.

Where the Rule Breaks Down

Not all drugs play nice with the 80-125% rule. Some need tighter limits. Others need looser ones.

Narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs like warfarin, levothyroxine, or phenytoin are dangerous if levels drift even slightly. Too little, and seizures or clots happen. Too much, and you bleed or go into toxicity. For these, the FDA now recommends a tighter range: 90-111%. Some countries require even stricter criteria.

Highly variable drugs are another problem. If a drug’s absorption varies wildly from person to person-like some epilepsy meds or antibiotics-the 80-125% range might be too strict. A 30% within-subject variability? That’s normal for some drugs. The EMA and WHO allow scaled average bioequivalence (SABE), which expands the range up to 69.84-143.19% for Cmax if the reference drug is highly variable. The FDA has similar pathways, but they’re harder to qualify for.

And then there are complex products: inhalers, topical creams, injectables, extended-release tablets. These don’t dissolve the same way in the body. The 80-125% rule was designed for simple oral pills. For complex generics, regulators are still figuring out how to measure bioequivalence. The FDA’s Complex Generics Initiative has spent $35 million since 2018 to solve this. New methods using in vitro testing and modeling are emerging-but they’re not yet standard.

Common Misunderstandings

Healthcare professionals get it wrong too. A 2022 survey found 63% of community pharmacists believed the 80-125% rule meant generics contain 80-125% of the active ingredient. That’s not even close. The rule measures systemic exposure, not drug content. The pill’s active ingredient is tightly controlled-within 5% of the label claim, same as brand.

Patients worry. Online forums are full of stories: “My generic seizure med didn’t work.” “I felt different after switching.” A Drugs.com thread from 2023 had 87 comments, and 62% of those cited the “80% rule” as their reason for distrust.

But data tells a different story. The FDA analyzed 2,075 generic drugs approved between 2003 and 2016. Only 0.34% required label changes due to bioequivalence issues after market approval. That’s less than 1 in 300. Most complaints come from formulation differences-fillers, coatings, release mechanisms-not the 80-125% rule itself.

Neurologists report occasional issues with generic anti-seizure drugs, but only 4% of those cases were linked to bioequivalence. The rest? Patient adherence, psychological factors, or unrelated drug interactions.

How the Rule Is Tested

Running a bioequivalence study isn’t simple. It typically involves 24-36 healthy volunteers in a crossover design: they take the brand drug, wait a washout period, then take the generic. Blood samples are taken every 15-30 minutes for 24-72 hours. The data gets log-transformed, analyzed using ANOVA, and the 90% CI is calculated.

Here’s what can go wrong:

- Using a 95% confidence interval instead of 90%

- Forgetting to log-transform the data

- Ignoring the requirement that both AUC and Cmax must pass

- Not accounting for food effects when the drug is taken with meals

- Allowing more than 20% outliers without justification

Entry-level researchers struggle with this. A 2021 survey found only 38% could correctly interpret the results without help. That’s why training programs like AAPS’s Bioequivalence Boot Camp exist-and why regulatory agencies publish detailed guidance documents.

The Bigger Picture

The 80-125% rule isn’t perfect. It’s a compromise. It was born from expert opinion, not hard clinical trials. But it’s held up for nearly 40 years. A 2022 meta-analysis of 214 studies confirmed: drugs meeting this standard show no clinically meaningful differences in outcomes across 37 drug classes.

Still, the future is changing. The FDA is investing $15 million to explore model-informed bioequivalence-using computer simulations to predict how a drug behaves without testing in humans. Pharmacogenomics may one day require personalized bioequivalence thresholds based on how fast someone metabolizes a drug. For now, though, the rule remains the global gold standard.

It’s not about trust. It’s about science. And for the vast majority of drugs, the 80-125% rule does exactly what it was designed to do: keep patients safe, keep costs low, and make life-saving medications accessible to everyone.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does the 80-125% rule mean generic drugs have less active ingredient?

No. Generic drugs must contain the same amount of active ingredient as the brand-name version-typically within 95-105% of the labeled amount. The 80-125% range applies to the body’s exposure to the drug (measured as AUC and Cmax), not the drug content in the tablet.

Why is a 90% confidence interval used instead of 95%?

The 90% confidence interval allows for a 5% risk of error on each side of the range, totaling 10% overall. This is the accepted regulatory standard because it balances statistical rigor with clinical practicality. A 95% CI would be too strict and could reject bioequivalent products unnecessarily.

Are all generic drugs required to meet the 80-125% rule?

Most are, but exceptions exist. Narrow therapeutic index drugs (like warfarin or levothyroxine) often require tighter limits (90-111%). Highly variable drugs may use scaled bioequivalence methods that allow wider ranges. Complex products like inhalers or extended-release tablets may follow different testing protocols.

Can I trust my generic medication if it passed the 80-125% rule?

Yes. Over 14,000 generic drugs in the U.S. have met this standard, and post-market surveillance shows fewer than 0.4% required label changes due to bioequivalence issues. The rule has proven reliable across decades and thousands of drugs. Concerns about effectiveness usually stem from other factors-not the 80-125% rule itself.

Why do some people feel different on a generic drug?

The 80-125% rule ensures the drug reaches your bloodstream the same way. But inactive ingredients-fillers, coatings, dyes-can affect how quickly the pill dissolves or how it’s absorbed. For most people, this doesn’t matter. But for sensitive individuals (like those with epilepsy or heart conditions), even small changes in release timing can cause noticeable effects. That’s why some doctors prefer to keep patients on the same generic brand.

David Cunningham

November 23, 2025 AT 04:33Been taking generics for years and never had an issue. My blood pressure med works fine, my antidepressant works fine. If it passes the 80-125 rule, it's good enough. Stop overthinking it.

Rahul Kanakarajan

November 23, 2025 AT 10:25LOL so now we're supposed to trust a statistical trick that lets Big Pharma save billions while we're told the pills are 'the same'? Please. I've seen people switch and crash. It's not science, it's corporate math.

Ravi Kumar Gupta

November 24, 2025 AT 06:31Bro, in India we get generics that cost 1/10th of the brand and they work just fine. My uncle took generic warfarin for 5 years, INR stayed stable. You think this is some Western conspiracy? Nah. It's just good science. Stop being dramatic.

Holly Schumacher

November 25, 2025 AT 20:42Actually, the 90% CI is not 'stricter'-it's mathematically less rigorous than a 95% CI, which is why the FDA uses it: to approve more generics faster. This isn't about safety-it's about regulatory convenience disguised as science. And don't even get me started on the fact that they don't test for metabolites.

Jessica Correa

November 27, 2025 AT 20:32I get why people worry but honestly the data is solid. My sister switched from brand to generic levothyroxine and her TSH didn't budge. The real issue is switching brands every time the pharmacy changes. That's when people get messed up-not because of the 80-125 rule.

james lucas

November 28, 2025 AT 20:07okay so i just read this whole thing and i think i get it now. so its not that the pill has less stuff in it, its how fast your body soaks it up. like if you drink coffee black vs with milk, same caffeine but different vibe. and the 80-125 is like the range where it still gives you the same buzz without making you jittery or sleepy. and yeah i used to think it was a scam but now i get why it works. thanks for explaining it so clearly

Shawn Daughhetee

November 29, 2025 AT 10:06My dad's on phenytoin and they switched his generic and he had a seizure. Not because of the rule, but because the pharmacy changed the filler and it changed how fast it dissolved. So yeah the 80-125 rule works for most drugs but for NTI stuff? You gotta be careful. My doc now keeps him on the same brand every time

New Yorkers

December 1, 2025 AT 06:34It’s funny how we’ve turned medicine into a math problem. We reduce life, death, and biochemistry to confidence intervals like it’s a spreadsheet. The 80-125 rule is a beautiful compromise-but it’s still a compromise. We treat patients like data points, not humans. And that’s the real tragedy.

Nikhil Chaurasia

December 2, 2025 AT 01:40I respect the science, but I’ve seen too many patients confused when their generic looks different. Even if it works, the anxiety alone can mess with adherence. Maybe we need better labeling-like a little badge that says 'FDA Bioequivalent' so people don't freak out when the pill color changes.

manish chaturvedi

December 3, 2025 AT 04:23As a pharmacist in Delhi, I can confirm: the 80-125 rule is the backbone of affordable healthcare in developing nations. We dispense over 200 generics daily. The failure rate is less than 0.1%. The real enemy is misinformation-not the regulation. Education, not suspicion, is what we need.

Michael Fitzpatrick

December 3, 2025 AT 06:51Man I remember when I first heard about this rule I thought it was wild too. Like how can you say two things are the same if one could be 20% less effective? But then I dug into the pharmacokinetics and realized-ohhh the log scale flips everything. Like if you think of it as a sound level, 80% isn't half as loud, it's like a subtle shift in tone. And the fact that they test both AUC and Cmax? That’s smart. It’s not just about total dose, it’s about timing too. And honestly? The data backs it. I’ve seen studies where they gave people brand vs generic and measured actual seizure control. No difference. It’s not magic, it’s math that works.

Holly Schumacher

December 3, 2025 AT 23:18Shawn, you said your dad had a seizure after switching generics-that’s tragic, but it’s not the 80-125 rule’s fault. It’s the pharmacy’s fault for switching without consulting the prescriber. The rule doesn’t allow for interchangeability of NTI drugs without additional testing. You’re blaming the system, not the implementation. And if your dad’s on phenytoin, he should be on a single manufacturer’s product for life. Period.