Generic drugs save patients and the healthcare system billions every year. In the U.S., 90.7% of all prescriptions are filled with generics - but not all generics are created equal. For pharmacists, knowing when to pause, question, and flag a generic substitution isn’t optional. It’s a critical safety duty.

Why Generic Drugs Can Go Wrong

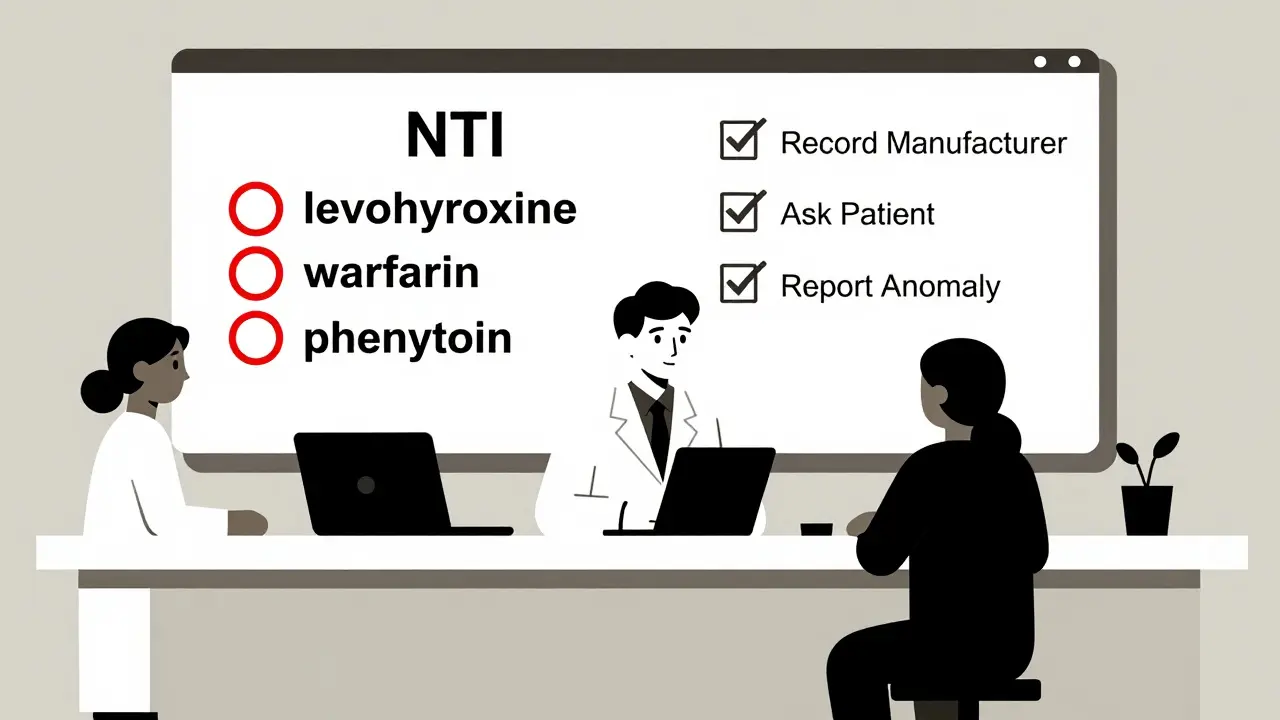

The FDA requires generics to match brand-name drugs in active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration. They must also prove bioequivalence: their blood levels must fall within 80-125% of the brand’s. That sounds tight - until you realize that’s a 20% variation allowed in how much drug actually enters your bloodstream. For most medications, that’s fine. A 10% difference in cholesterol levels from a generic statin? No big deal. But for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index - where the difference between effective and toxic is razor-thin - that 20% gap can be deadly. Take levothyroxine. A patient stable on one generic manufacturer’s version might see their TSH jump from 2.1 to 8.7 after switching to another. That’s not a fluke. It’s a documented pattern. The same goes for warfarin, phenytoin, and digoxin. These are not theoretical risks. They’re real, preventable events.The 5 Situations When Pharmacists Must Flag a Generic

- Therapeutic failure after a switch - If a patient reports their condition worsening within 2-4 weeks of switching to a new generic, especially with NTI drugs, don’t assume it’s noncompliance. Document the manufacturer and contact the prescriber immediately.

- Unexplained side effects - A patient says, “This new pill makes me dizzy” or “My stomach is wrecked” after a switch. That’s not just “bad luck.” It could be a different inactive ingredient, dissolution rate, or coating causing irritation or altered absorption.

- Look-alike, sound-alike confusion - Oxycodone/acetaminophen and hydrocodone/acetaminophen look identical on the bottle. So do metoprolol succinate and metoprolol tartrate. If the label or pill shape changed unexpectedly, verify the manufacturer and confirm with the patient.

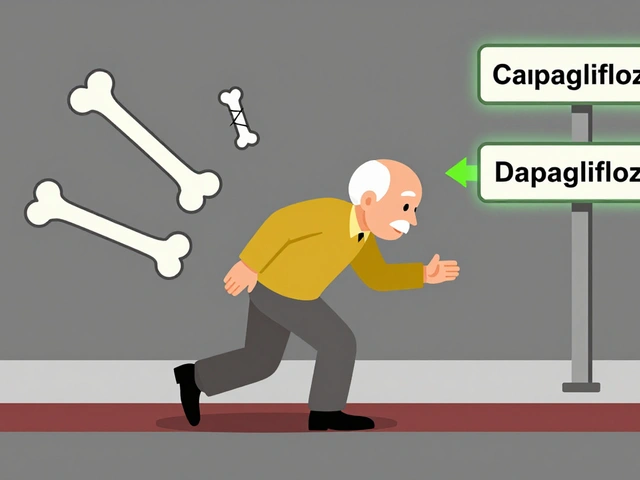

- Complex formulations - Extended-release, delayed-release, or transdermal generics are harder to copy. In 2020, FDA testing found 7.2% of generic extended-release opioids failed dissolution tests. That means the drug didn’t release properly - leading to underdosing or dangerous spikes.

- Multiple switches in a short time - If a patient gets switched between three different generic manufacturers in six months, their body never stabilizes. Studies show this increases therapeutic failure risk by 2.3 times for NTI drugs.

What the FDA and Experts Say

The FDA insists generics are safe. Dr. Janet Woodcock, former head of the FDA’s drug center, stated clearly: “The FDA requires generic drugs to have the same quality, strength, purity, and stability as brand-name drugs.” But even the FDA acknowledges problems. Their Orange Book lists 10.3% of generic drugs as “BX” - meaning they’re not rated as therapeutically equivalent. Why? Because bioequivalence data was incomplete or inconsistent. And then there’s the data from MedWatch. Between January 2021 and March 2022, 47 cases of therapeutic failure were linked to a specific generic version of diltiazem CD. That’s not a glitch. That’s a pattern. The FDA issued a Drug Safety Communication. Pharmacists who flagged it early prevented harm. Dr. Michael Cohen of the Institute for Safe Medication Practices says look-alike/sound-alike errors cause 14.3% of all generic medication mistakes. That’s one in seven. And in a 2022 survey, 63.2% of pharmacists reported encountering a problematic generic substitution in the past year. Nearly 30% saw patient harm.

How Pharmacists Can Protect Patients

You don’t need to be a pharmacologist to spot trouble. You need a system.- Check the Orange Book - Always verify the therapeutic equivalence code. If it’s “BX,” flag it. Don’t assume the prescriber knows.

- Record the manufacturer - Every time you dispense a generic, write down the manufacturer name. If a problem arises, you’ll need it. Studies show 68.4% of therapeutic failure investigations require manufacturer-specific data.

- Ask patients directly - “Has anything changed since you started this new pill?” is a better question than “Are you taking it okay?”

- Use therapeutic drug monitoring - For drugs like tacrolimus, phenytoin, or warfarin, check blood levels before and after a switch. A 20% change in concentration isn’t normal - it’s a red flag.

- Report it - Use the FDA’s MedWatcher app or ISMP’s reporting system. One report might seem small. But 10 reports? That’s a trend. And trends trigger FDA investigations.

State Laws and Real-World Barriers

In 29 states, pharmacists are legally required to substitute generics unless the prescriber says “dispense as written.” In 17 states, substitution is presumed unless the patient objects. That puts pressure on pharmacists to fill the cheapest option - even when it’s risky. But in four states - Massachusetts, New York, Texas, and Virginia - pharmacists must get special permission before substituting NTI drugs. That’s the right approach. These drugs aren’t like ibuprofen. They’re like insulin. One wrong dose can kill. The problem? Many pharmacists don’t know the rules in their own state. Continuing education on generics is mandatory in only 32 states. That’s not enough. This isn’t just about cost. It’s about trust.

The Bigger Picture

The generic drug industry is huge - $135.7 billion globally in 2022. Most of it is safe. Most patients are happy. Consumer Reports found 78.3% of patients are satisfied with generics, mostly because they save money. But that 22.4% who report different side effects? That’s over 1 in 5. And the FDA’s Patient-Focused Drug Development program collected 1,842 complaints between 2020 and 2023. Over a third were about inconsistent effectiveness. That’s not noise. That’s a signal. The FDA is responding. Their new GDUFA III plan allocates $1.14 billion over five years to improve post-market surveillance. They’re increasing sampling of generics by 40% over the next three years. They’re using AI to detect patterns in adverse event reports. But none of that replaces the pharmacist at the counter. You’re the last line of defense.What You Can Do Today

- Open your pharmacy’s formulary and highlight all NTI drugs. Put a red dot next to them. - Print a list of look-alike/sound-alike generic pairs and post it near the counter. - Ask your pharmacy tech to log every generic manufacturer in the dispensing system. - Talk to your patients. Don’t assume they’ll tell you if something’s wrong. Ask. - Report every suspicious case. Even if you’re not sure. The system only works if you use it. Generic drugs are a triumph of public health. But they’re not perfect. And when they fail, it’s not because the science is broken. It’s because we stopped paying attention. You don’t need to stop dispensing generics. You just need to know when to stop and think.Are all generic drugs safe?

Most are. Over 90% of prescriptions in the U.S. are filled with generics, and the vast majority work just as well as brand-name drugs. But not all are equal. Some generics - especially for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index like levothyroxine or warfarin - can vary in how they’re absorbed. The FDA allows up to a 20% difference in blood levels, which can matter for sensitive medications. Always check the manufacturer and report unusual reactions.

What is a narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drug?

An NTI drug has a very small window between the dose that works and the dose that causes harm. Small changes in blood levels can lead to treatment failure or serious side effects. Examples include levothyroxine, warfarin, phenytoin, digoxin, and tacrolimus. Switching between generic versions of these drugs increases risk. Pharmacists should avoid unnecessary switches and monitor blood levels closely.

Can a generic drug be less effective than the brand?

Yes - but not because the active ingredient is weaker. The issue is often in how the drug is released. Extended-release or delayed-release generics sometimes don’t dissolve properly due to differences in fillers, coatings, or manufacturing. For example, a 2020 FDA study found 7.2% of generic extended-release opioids failed dissolution tests. Patients may not get enough drug, or they may get a sudden spike. That’s why tracking the manufacturer matters.

Why do some patients say their generic pills look different?

Generic manufacturers are not required to match the brand’s pill color, shape, or size. That’s why patients often notice a change when their prescription is refilled. Sometimes it’s just a different manufacturer. But if the patient reports new side effects or worsening symptoms after the pill looks different, that’s a red flag. Always ask: “Did anything change since your last refill?”

Should pharmacists refuse to dispense a generic if the patient is stable?

If a patient is stable on a specific generic brand - especially for an NTI drug - it’s often safer to keep them on it. Many states allow pharmacists to dispense the brand or specific generic if requested. Even if substitution is mandatory, pharmacists can note “dispense as written” if they believe switching poses a risk. Your clinical judgment matters. Don’t let policy override patient safety.

How can I report a problematic generic?

Use the FDA’s MedWatcher app - it takes less than five minutes. Or report through the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) National Medication Errors Reporting Program. Include details: drug name, manufacturer, patient symptoms, and when the issue started. One report might not change anything. But 10 reports? That’s a pattern the FDA will investigate. Your report could prevent harm to someone else.

Jenny Salmingo

December 31, 2025 AT 06:08My grandma switched generics for her thyroid med and started feeling like a zombie. Took three months to figure out it was the brand change. Now we only get the one with the blue pill. Simple as that.

Pharmacists should ask more. Patients don’t know to tell them.

Thanks for saying this.

Aaron Bales

January 1, 2026 AT 01:53NTI drugs need stricter rules. Period. 20% variation is a loophole disguised as policy. If you’re dosing warfarin or digoxin, you’re not buying cereal-you’re handling a scalpel. Track manufacturers. Log everything. Report anomalies. That’s not extra work-it’s standard care.

Sara Stinnett

January 1, 2026 AT 09:28Oh please. The FDA is a puppet of Big Pharma and Big Generic alike. They ‘approve’ generics based on lab rats in a petri dish, then wonder why people get sick. You think a 20% variance is acceptable? Try living with seizures because your phenytoin didn’t dissolve right. This isn’t science-it’s corporate roulette.

And don’t get me started on ‘look-alike’ pills. That’s not negligence. That’s negligence with a corporate logo.

linda permata sari

January 1, 2026 AT 22:21OMG I JUST HAD THIS HAPPEN TO ME!! 😭 I was on the same levothyroxine for 5 years, then one day my pill was pink instead of white-and suddenly I couldn’t get out of bed. My doctor said ‘it’s the same drug’ but NO IT WASN’T. I cried for three days. I finally found my old brand on a website and ordered it from Canada. Worth every penny. Please, pharmacists-ASK THE PATIENTS!!

Brandon Boyd

January 3, 2026 AT 09:24Hey, if you’re a pharmacist reading this-you’re doing God’s work. Seriously.

Most people don’t realize how much you carry. You’re the last line between someone feeling okay and ending up in the ER.

Keep doing what you’re doing. And if you’re not already logging manufacturers? Start today. One note could save a life. You’re not just filling scripts-you’re holding the line.

Branden Temew

January 3, 2026 AT 11:04So we’re supposed to trust the FDA, but also not trust the FDA? Interesting. They say generics are safe, then admit 10% are BX-rated. They say ‘bioequivalence’ is good enough, then ignore 47 cases of diltiazem failure.

It’s like saying ‘this airplane has a 99% safety rating’ while ignoring the one that crashed last week.

Maybe we should stop pretending the system works. It’s just… convenient.

Paul Huppert

January 5, 2026 AT 06:45My mom’s on warfarin. We always write down the manufacturer now. No joke-last time they switched and her INR went nuts. Took a week to stabilize. Now we just ask the pharmacist: ‘Same maker as last time?’

Simple. Free. Works.

Hanna Spittel

January 6, 2026 AT 08:31ALERT 🚨 This is why I don’t trust ANY generic anymore. 👁️🗨️ They’re all made in India or China and no one checks! I saw a video of a pill factory with rats running through the aisles. I’m switching to brand. Even if it costs $300. I’d rather pay than die. 💀💊

John Chapman

January 7, 2026 AT 18:12STOP acting like this is some new problem. Pharmacists have been fighting this for DECADES. The system is rigged to push the cheapest pill, no matter the cost.

But here’s the truth: YOU have power. You can say ‘dispense as written.’ You can report. You can refuse.

Don’t be silent. Your silence is what kills people. 🙏

Robb Rice

January 8, 2026 AT 13:08While I appreciate the intent of this post, I must note that the FDA’s GDUFA III funding allocation is actually $1.14 billion over five years for generic drug facility inspections-not specifically for post-market surveillance. The language here is slightly misleading, and accuracy matters when discussing regulatory policy. That said, the core message is sound: vigilance saves lives.

Harriet Hollingsworth

January 10, 2026 AT 09:42This is why we can’t have nice things. People want cheap medicine but then cry when it doesn’t work. If you want the brand, pay for it. Don’t blame the pharmacist. Don’t blame the FDA. Blame yourself for wanting $4 pills with the same effect as $400 ones. It’s not magic. It’s chemistry. And chemistry costs money.

Deepika D

January 10, 2026 AT 16:56As a pharmacist in India, I can tell you this issue is global. We have the same problems-patients switching generics every month because insurance changes, manufacturers changing without notice, no tracking systems in place. We don’t even have an Orange Book equivalent here. We rely on word-of-mouth among pharmacists and patient feedback. I’ve seen patients go from seizure-free to having daily convulsions after a switch. We report to the national drug authority, but it takes months for anything to happen. The system is broken everywhere. We need global standards. Not just U.S. fixes. We need to treat medicine like life-not like a commodity. Every pill matters.

Bennett Ryynanen

January 12, 2026 AT 08:36My cousin’s dad died from a generic digoxin switch. No one knew. No one reported. Just assumed he ‘got worse.’ That’s not a tragedy. That’s a failure. And it’s on all of us. Stop being passive. If you see it, say it. If you’re a pharmacist-speak up. If you’re a patient-ask questions. If you’re a doctor-write ‘dispense as written.’ Don’t wait for someone else to fix it. Fix it now.

Stewart Smith

January 14, 2026 AT 00:52Fun fact: the same generic manufacturer that made the bad diltiazem? Also makes the good one. It’s not about country or company-it’s about batch. One bad batch can ruin trust. That’s why logging every single one matters. Not because they’re evil. Because they’re human. And humans make mistakes.

Retha Dungga

January 14, 2026 AT 18:43the system is rigged and we all know it 🤷♀️ nobody cares until someone dies then its like oh no what happened 🤡 why do we even pretend this is healthcare